This is part of an ongoing series from Ken Hensley. Read previous installments: Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V Part VI Part VII Part VIII Part IX Part X

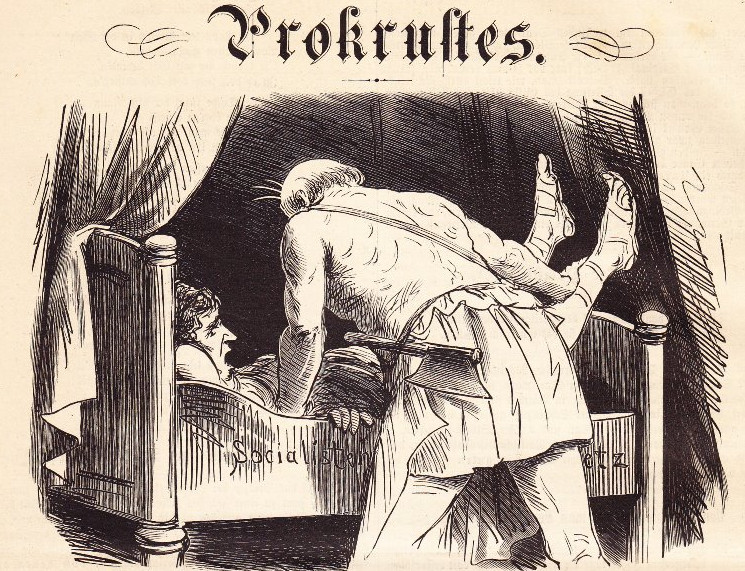

One of the more curious figures from Greek mythology is a fellow named Procrustes. Apparently, Procrustes ran a little Bed & Breakfast on the road between Athens and Eleusis. When travelers made their way past his lair, he would invite them in for a pleasant meal and rest for the night. He had a special bed, he explained, one they would surely want to try out—an iron bed that somehow matched exactly the length of every person who lay on it.

What Procrustes declined to mention was the unusual method by which this “one size fits all” miracle bed worked.

As soon as he had his guest where he wanted him, he would bring out his various tools and get to work. Those who were too short, he would stretch on the rack to make them longer. Those who were too tall, he would cut down to size, amputating as much of their feet and legs as was required to achieve the perfect length.

In the end, everyone fit the bed the Procrustes. He made sure of it.

Iron Beds and Worldviews

I think of Procrustes as the ultimate reductionist, and of those who advocate reductionist worldviews—worldviews that insist on reducing everything to “one essential thing”—as his philosophical disciples. Inevitably, they’re forced to torture reality in order to make it fit the iron bed of their pre-determined schema.

In particular, I think that what Procrustes did to his guests all reductionist worldviews do to the richness of human experience—only much worse! It’s inevitable that when all of reality is viewed as reducible to “one essential thing,” and when one is committed to making sure that everything is made to fit that “one essential thing,” some serious torturing of human experience is going to have to take place—a little stretching here, a little whittling there.

Take for example the eastern pantheist who insists that everything is “God.” “Nothing exists but spirit,” he says, and when some unenlightened westerner scratches his fool head and says, “You know, it sure doesn’t seem like everything is spirit. I mean, what about this body I inhabit? What about these hands and feet and eyes and head?” the subtle eastern mystic responds, “Ah, but all that is illusion, you see. Material reality may seem to exist, but it really doesn’t. Beneath what appears to be, everything is spirit.”

The modern scientific materialist does exactly the same thing, only in reverse. “Everything is matter,” he insists. “Nothing exists but the material universe.” And when the unenlightened furrows his ignorant brow and complains, “But it sure doesn’t seem like everything is matter! I mean, what about the ideas I have in my head? What about the consciousness I have of myself as a person? I remember Christmas morning when I was seven, walking out into the living room and seeing my gifts under the tree. Is that memory entirely reducible to some electrochemical process taking place in my brain? What about love? What about the process of reasoning? Is reasoning a material process determined by chemical or physical laws?”

When we ask these questions the subtle materialist philosopher responds, “Ah, but nothing exists but matter. It is illusion to imagine that your mind is anything more than matter.”

As atheist Francis Crick has written,

You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules (The Amazing Hypothesis).

Along these same lines, Darwin referred to thoughts as “excretions of brain.”

The Iron Bed of Naturalism

On the one hand, the materialist philosopher and scientist speaks with full assurance that human beings are nothing but matter. At the same time they admit continually that they have no idea how consciousness could possibly arise from biological tissue. Not a clue.

And so Geoffrey Madell confesses in Mind and Materialism, “The emergence of consciousness is a mystery, and one to which materialism signally fails to provide an answer.” Notice, he doesn’t say that materialism has a hard time explaining the emergence of consciousness. He says it “signally fails” to explain the emergence of consciousness.

Likewise, materialist Jaegwon Kim asks in Philosophy of Mind, “How can a series of physical events, little particles jostling against one another, electric current rushing to and fro . . . blossom into a conscious experience?” He has no idea.

In his book The Mysterious Flame Atheist Colin McGinn expresses utter dumbfoundedness at the idea that human consciousness could somehow arise from the jostling of atoms:

How can mere matter originate consciousness? How did evolution convert the water of biological tissue into the wine of consciousness? Consciousness seems like a radical novelty in the universe…so how did it contrive to spring into being from what preceded it? It strikes us as miraculous, eerie, even faintly comic.

These are all good questions. As philosopher J.P. Moreland says in his wonderful book The Recalcitrant Imago Dei, “Start with matter and tweak it physically and all you get is tweaked matter.”

Consciousness strikes us as something explicitly non-material. It’s strikes us as something miraculous. But of course it can’t be because the materialist has already decided that nothing exists but matter.

Materialism Almost Certainly False

In 2012 well-known philosopher Thomas Nagel came out with a book in which he argues that what seems intuitively self-evident to us—that not everything is reducible to matter—is true.

If there ever was a provocative book title, this is it: Mind & Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False. Apparently, Professor Nagel, himself an atheist, has become bone-weary of naturalist philosophers and scientists forcefully asserting that human consciousness can be explained as reducible to electrochemical processes in the brain, assuring us this is the case, insisting that this must be the case.

No, he argues, consciousness—especially the subjective experience of being conscious of ourselves as individual persons with our own memories, experiences, intentions, desires—is such a fundamental characteristic of who we are as human beings, and stands out so conspicuously as distinct from matter, that it can no longer be merely asserted that consciousness is reducible to material processes.

It must, he says, be explained how it could possibly have evolved in a universe in which nothing exists but material substances.

Consciousness is the most conspicuous obstacle to a comprehensive naturalism that relies only on the resources of physical science. The existence of consciousness seems to imply that the physical description of the universe, in spite of its richness and explanatory power, is only part of the truth… If we take this problem seriously, and follow out its implications, it threatens to unravel the entire naturalistic world picture.

Now, Nagel admits freely that he does not want to believe in God. He doesn’t even like the idea of there being a god, and therefore being accountable to a god. At the same time, he has come to believe that full-strength materialism is “almost certainly false.”

He’s working on his own solution to the problem, one in which both mind and matter both exist as fundamental realities in a universe without God. (Good luck!) But at least he’s willing to face the reality that consciousness seems to amount to a recalcitrant fact, a fact that cannot be explained in terms of a worldview that reduces everything to physical particles and insists that nothing else exists.

The Religion of Naturalism

Nagel is entirely aware that the doubts he is expressing—doubts about the ability of materialism to account for human consciousness—will be received as pure heresy by those who offer incense and sacrifice in the temple of naturalism.

I realize that such doubts will strike many people as outrageous, but that is because almost everyone in our secular culture has been browbeaten into regarding the reductive research program as sacrosanct, on the ground that anything else would not be science.

I think that Nagel is correct. In fact, I believe that one of the most mischievous sleight of hand tricks to have ever been performed is the way in which naturalism, as a worldview, has somehow been slipped into modern consciousness on the coattails of science.

Of course, science has not demonstrated that materialism is true. Science never could even in principle demonstrate such a thing. But in the minds of a great many, this is precisely what “science” has demonstrated—that nothing exists but particles interacting according to unbending chemical and physical laws.

One would think that at some point the sheer weight of the implications of holding to a consistent materialist worldview would lead the atheist to take a second look. Even human consciousness is an illusion? Even the sense I have of being someone?

In a way, it’s almost humorous to think that while Procrustes only amputated the feet of his guests, the committed materialist amputates our heads—as well as his own!—in his determination to make everything fit the iron bed of his materialist worldview.

Thankfully, not everyone who might describe himself as an “unbeliever” or “atheist” or “agnostic” is really willing to allow his head to be chopped off for the sake of his faith in materialism.

Thankfully, not everyone is willing to accept that what amounts to the most basic and fundamental aspect of their experience as human beings—their sense of personal identity—is illusion and has been all along, that in reality they are nothing but biochemical machines, even their thoughts mere excretions of brain.

Thankfully, not everyone is willing to buy into the full implications of holding a materialist view of life.

These are people who may be willing to consider another worldview. These are people you begin a discussion with: Is it possible that consciousness is evidence that materialism isn’t true at all and that there’s more to this world than particles in motion? What if the truth is that there is a God and that you have been created in God’s image and likeness, that you possess a spiritual soul and that this is what accounts for the sense you’ve had all your life of being you? Wouldn’t you want to know this if it were true?

Up Next: How I Evangelize Those Who Doubt or Deny the Existence of God, Part XII