This article is part of an ongoing series from Ken Hensley. Part I Part II Part III

In 1980, I was a young seminary student for whom nothing was more exciting than thinking about the truths of the Christian Faith.

At the time I was a firm believer in Luther’s doctrine of justification by faith alone: sola fide. The instant one looks to Christ in faith, I believed, “justification” takes place and is completed. Christ’s own perfect righteousness is legally credited to the account of the one who only believes, and one is saved — past tense!

After this I believed, along with Luther, Calvin, and classical Protestantism, that one who has been justified will want to obey the commandments of Jesus. He will want to obey, but not because obedience is a part of what is required in order to receive eternal life. He will want to obey as an act of gratitude for having been saved.

But I was also a committed advocate of sola Scriptura, wide-open to any and all arguments that could be made from the Bible. And, having something of the mindset of a theological detective, I was continually measuring exegetical footprints in the sands of Scripture, powdering the pages of St. Paul’s writings for doctrinal fingerprints, examining the shapes of ideas and arguments, on the lookout for patterns of textual evidence.

A Peculiar Biblical Pattern

And then something happened.

One of my professors at Fuller Theological Seminary — he was extremely bright, having academic PhD’s in both Old and New Testaments — was talking one day about Luther, Calvin, and justification by “faith alone.”

All of a sudden a puzzled look came over him and he said, “You know, it’s a curious thing, but when you think of it, the Bible is essentially one story after another of men and women and their relationships with God, one illustration after another of how God relates to His people. And never in these stories do we find God telling people that they will receive His blessing by ‘faith alone.’

Rather, the pattern is always ‘trust me (faith); do what I tell you to do (obedience), and I will bless you.’ The basic pattern in Scripture is always faith, leading to obedience, resulting in blessing.”

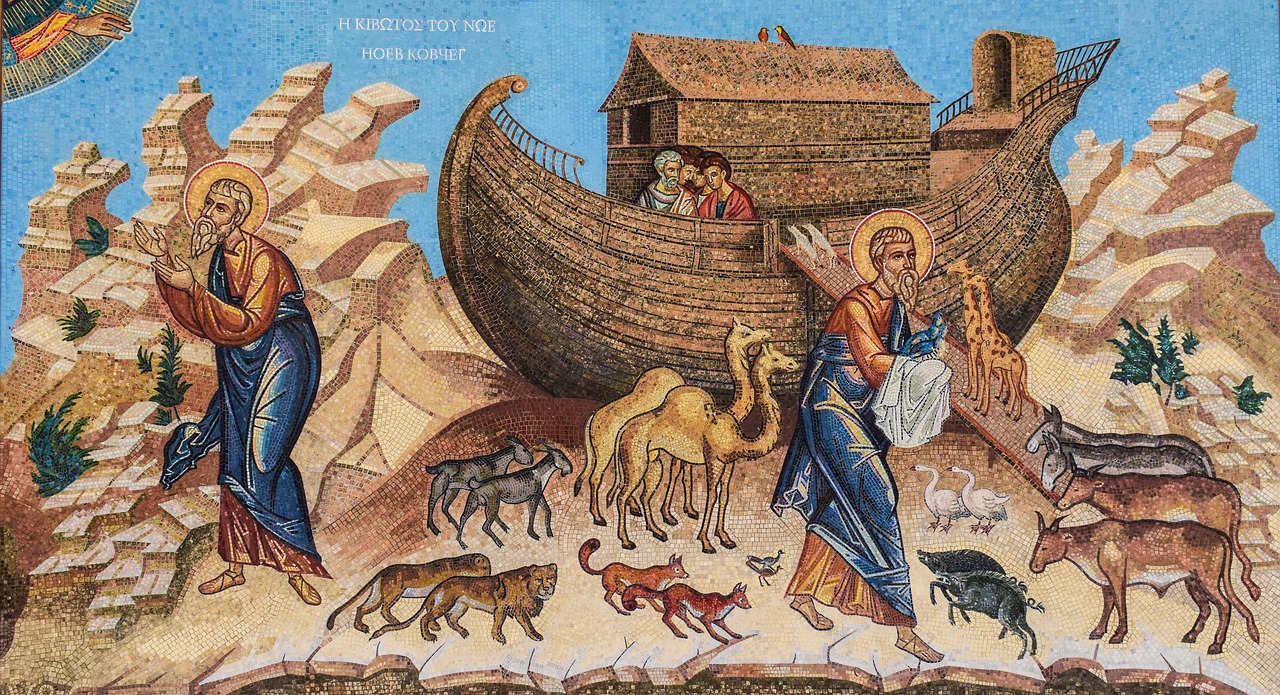

He went on to offer some illustrations from the Bible: “Noah had to trust God,” he said, “and build the ark in order to be saved through the flood. Certainly, faith was at the heart of Noah’s response; he would never have built the ark if he hadn’t first believed God’s warning to him. But it wasn’t ‘faith alone’ because if he hadn’t built the ark, he wouldn’t have been saved. Clearly, the pattern we see is faith, leading to obedience, resulting in deliverance.”

He went on: “Abraham had to trust God and leave his home and family in Mesopotamia and follow, in order to receive the blessings God had promised him. It wasn’t faith alone. It was faith, leading to obedience, resulting in blessing.

Moses and the children of Israel had to trust God and sacrifice the Passover lamb and leave Egypt and cross the Red Sea and follow the pillar of cloud by day and fire by night and eat the manna each day and bring their sacrifices to the priest when they sinned and cross the Jordan and take the cities one by one — in order to inherit the Promised Land. No ‘faith alone,’ here!

Naaman the Syrian had to trust God, and dip himself seven times in the Jordan River, in order to be cleaned of his leprosy.

The man blind from birth had to trust Jesus and wash in the Pool of Siloam, in order to receive his sight.”

I remember being struck by how simple it was to find illustrations of this basic pattern of “faith, leading to obedience, resulting in blessing.” It was on every page of the Bible.

It seemed clear to me that my professor was correct.

The Protestant Pattern

Now, what troubled my professor was that the pattern we see in the Protestant doctrine of sola fide does not fit the pattern we see illustrated in Scripture. In the Protestant view of how God deals with people, the pattern is entirely different.

- We believe in Christ (faith).

- We are immediately justified (blessing).

- And then we proceed to live out our faith (obedience) as an act of gratitude to God for having saved us (past tense).

According to the pattern we see in Scripture, obedience is always a part of what was required in order to receive God’s promised blessing. To be saved through the flood, Noah had to actually build the boat. To become the father of a multitude, Abraham had to actually leave Ur of the Chaldees. To be delivered from slavery in Egypt, Moses and the Israelites had to actually do what God gave them to do. To be cleansed of his leprosy, Naaman had to actually go and dip himself in the Jordan seven times. To receive his sight, the man born blind had to actually wash himself in the Pool of Siloam.

Now, according to Luther, Calvin, and Protestantism, obedience is no longer a part of what is required in order to receive the blessing.

This troubled my professor — and it troubled me.

“If God wanted to teach the world that His blessings are to be received by ‘faith alone,’ why,” he wondered, “did God fill the entire Bible with the stories of men and women who never receive His blessings by faith alone?”

One Failed Objection

As a Protestant, here’s the answer I was tempted to give to my professor’s question: “The pattern we see in the lives of these people in the Old Testament doesn’t apply to us. They lived under a system of works; we live under a system of grace.”

Except … if this were true, why are these Old Testament saints set forth in the New Testament as examples for us to emulate?

For instance, in Hebrews 11 the author scans salvation history from the beginning and presents his readers with example after example of men and women he clearly wants them to imitate.

And every one of these examples illustrates the pattern of faith, leading to obedience, resulting in blessing.

By faith Abel offered to God a more acceptable sacrifice than Cain, through which he received approval as righteous (11:4).

By faith Noah, being warned by God of events as yet unseen, took heed and constructed an ark for the saving of his household (11:7).

By faith Abraham obeyed when he was called to go out (11:8).

By faith [Moses] left Egypt (11:27).

By faith the people crossed the Red Sea as if on dry land (11:29).

By faith Rahab the harlot did not perish with those who were disobedient, because she had given friendly welcome to the spies (11:31).

In short, the author of Hebrews parades before his readers example after example of men and women who trusted God and did what God told them to do and were blessed because of this.

But, as a Protestant, I would have expected the author to immediately add, “But please ignore all these examples because, after all, these men and women were living under a system of ‘works,’ and we are living under a system of ‘grace.’ They were required to obey God in order to receive His blessings and so their example doesn’t really apply to us.”

But what, instead, does the author of Hebrews immediately say?

Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight, and sin which clings so closely, and let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us.

And then he brings forth the greatest example there is of faith, leading to obedience, resulting in God’s blessing:

Looking to Jesus the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God (Hebrews 12:1-2).

No. It was perfectly clear to me that the author of Hebrews wanted me to imitate Noah and Abraham and Moses and Jesus. As these all walked in the obedience of faith and received God’s blessing because of it, it was clear to me that God wanted me to do the same.

It was clear that the author of Hebrews sees a continuum between their way and ours. He’s not drawing a contrast. Not in the least.

Calling Good Evil

But here’s the thing that really twisted my head into knots.

Not only does Protestantism insist that the pattern we see illustrated in the lives of these Old Testament saints — and set forth for us to imitate in Hebrews 11! — no longer applies to Christians, it insists that this pattern be rejected as the essence of “legalism.”

As a Protestant seminarian, I believed this to be the case. Announce to any serious Protestant that you believe a Christian must persevere in faith and obedience in order to receive eternal life, and you will be informed that you are preaching “legalism” and have embraced a “damning system of works-righteousness.”

This was more than a decade before I ever contemplated the idea that the Catholic view of salvation might be the biblical view. But I knew, even back then, that there must be something wrong with the logic of Protestantism if it could lead to the conclusion that Noah and Abraham and all the Old Testament saints — and Jesus Himself! — are examples of a legalistic way of relating to God the Father.

The Problem Of Boasting

“But Ken, don’t you realize that if our obedience is in any sense — and to any degree — required in order for us to inherit eternal life, then we will to that degree have earned our own salvation? Then salvation will not be entirely the work of God. Then Christ our Lord will not receive all the glory for the great work of salvation. Then will we not have reason to boast that to some degree we saved ourselves?”

This line of reasoning runs as a thread through every classic presentation of the argument for sola fide. I had heard this argument all my Christian life. But now, reflecting on the fact that all those Old Testament saints had to obey in order to be blessed and then are presented to New Testament believers as role models, another set of rhetorical questions began to ask themselves:

So does this mean Noah saved himself from the flood?

Does this mean God didn’t get all the glory for Noah’s deliverance through the flood? Are God and Noah splitting the glory on that one?

Does this mean that Moses is in heaven boasting for all eternity that he delivered the children of Israel out of bondage in Egypt?

Is the man born blind bragging forever that he “earned” his eyesight by his “work” of washing in the Pool of Siloam?

The questions answered themselves.

Conclusion

It would be another dozen years before I would begin to examine seriously the Catholic teaching on justification. But I knew even then that there was something wrong with the logic of sola fide.

In time I was ordained into the Protestant ministry. I spent the next ten years preaching that we are saved by the grace of God as we trust God and do what He says and persevere in this obedience of faith to the end of our lives. Faith, leading to obedience, resulting in blessing.

I must confess it was quite a surprise when I realized that I had been preaching, essentially, the Catholic view of salvation.