This article is part of an ongoing series from Ken Hensley. Part I Part II

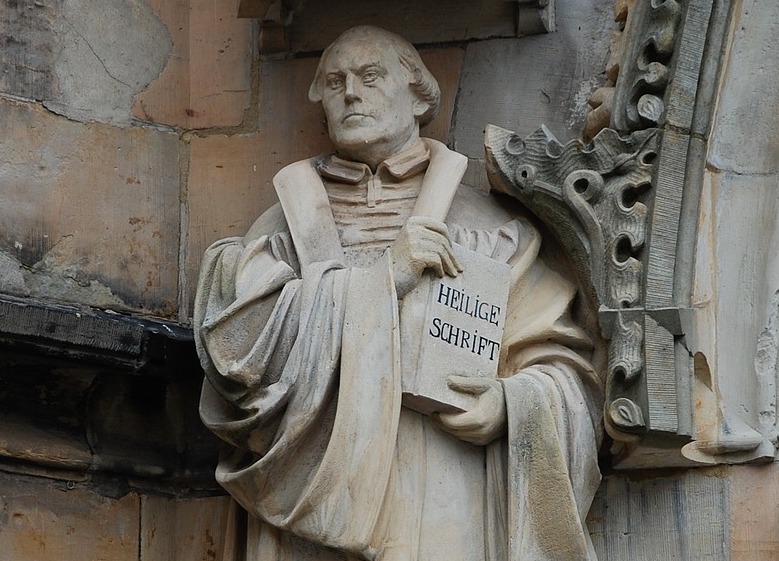

In 1512 Martin Luther received his doctorate and took his seat as professor at the University of Wittenberg. Between 1513 and 1516 he lectured through the Psalms and St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans.

It was during this time that Luther discovered something in St Paul, something that changed everything for him — and for the Church of the late Middle Ages as well. While Luther’s “discovery” provided an answer to his own deep spiritual struggle, it also led to the fracturing of Christianity which has persisted to this day.

Wrestling with Romans

Luther was struggling with the meaning of St. Paul’s words in the first chapter of Romans, verses 16 and 17:

For I am not ashamed of the gospel: it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek. For in it the justice of God is revealed from faith to faith; as it is written, “The just shall live by faith.”

Luther was wrestling with the fact that this passage seemed to him to contain simultaneously both “good news” and “bad news.” On the one hand, St. Paul was describing the “gospel,” the “good news.” On the other hand … well, here’s how Luther put it:

I greatly longed to understand Paul’s epistle to the Romans and nothing stood in the way but that one expression, “the justice of God,” because I took it to mean that justice whereby God is just and deals justly in punishing the unjust. My situation was that, although an impeccable monk, I stood before God as a sinner troubled in conscience, and I had no confidence that my merit would assuage him. Therefore I did not love a just and angry God but rather hated and murmured against him.1

How, Luther wondered, could it be “good news” to say that the justice [or righteousness] of God is being revealed? Is it good news that God is going to condemn me as unrighteous?

A Flash of Light from Heaven

As Luther strained to understand what Paul was saying, he fixed his mind on the connection the Apostle makes between the “justice of God” and Paul’s statement that “the just will live by faith.”

Suddenly, it came to him that the justice (or righteousness) of God that Paul says is being revealed in the gospel is not the righteousness by which God will judge the guilty, but rather the righteousness God will simply give to those who only believe.

For Luther, this realization came like a flash of light from heaven: the good news is that righteousness is offered as a free gift to be received by faith alone. The moment we believe, we put on Christ’s righteousness like a man might put on a cloak, and from that moment, we are, in God’s eyes, as righteous as Christ Himself. We are pronounced “just.” We are justified.

A few years later Luther would use this very image in one of his most famous works, The Freedom of the Christian. Luther wrote, “Christ has suffered for our sins and has fulfilled the law for us. We have only to believe in Him, and by believing in Him, take hold, as it were, of his merits and put them on like a cloak.”2

Luther referred to this as the “glorious exchange.” We give Christ our sins; He gives us His perfect righteousness.

This was Luther’s Damascus Road experience:

Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through open doors into paradise. The whole of Scripture took on a new meaning, and whereas before the “justice of God” had filled me with hate, now it became to me inexpressibly sweet in greater love. This passage became to me a gate to heaven.3

The importance of sola fide

Justification by faith alone (sola fide) was the central doctrinal issue for Luther. His eventual rejection of the entire sacerdotal and sacramental system of the Catholic Church was rooted in this one thought: the righteousness you and I must possess to enter heaven is not a righteousness God works in us as we cooperate with His grace and are remolded over time into the image of Christ (essentially, the Catholic view); rather it is what Luther referred to as an “alien righteousness,” a righteousness that comes from “without” and that is “accounted” to us the moment we believe. It is Christ’s own righteousness.

Now, Luther’s commitment to sola fide was total. It was the article of faith, he said, “upon which the church stands or falls.”

He interpreted all of Scripture in the light of his new teaching. Indeed, he was willing to question the inspired authority of any New Testament book that didn’t seem to him to agree with it — for instance, the Epistle of St. James.

Because James says in 2:24, “You see that a man is justified by deeds and not by faith alone!” Luther responded:

Away with James! Its authority is not great enough to cause me to abandon the doctrine of faith … If they [referring to other teachers] will not agree to my interpretations, then I shall make rubble of it. I almost feel like throwing Jimmy into the stove. It is flatly against St. Paul and all the rest of Scripture in ascribing justification to works … Therefore I do not want him in my Bible.4

Luther went so far as to assert that no one could be saved who did not agree with him on this crucial issue of justification.

I do not admit that my doctrine can be judged by anyone, even the angels. He who does not receive my doctrine [of sola fide] cannot be saved.5

Are Catholics even Christians?

It might surprise you to know that this is still how the most serious Reformation-minded Protestants feel about this issue of justification by faith alone — that it’s doubtful one could be saved who doesn’t understand and believe it.

I have a book in my library titled Justification by Faith Alone: Affirming the Doctrine by which the Church and the Individual Stands or Falls. In this book a number of contemporary Protestant scholars contribute chapters on various aspects of the doctrine of sola fide.

In a chapter titled “Rome NOT Home,” Dr. John Gerstner writes about the conversion to the Catholic Faith of his former seminary student Scott Hahn. He describes how he “mourned” for Scott when he learned of it. Why? Because he believed that no one could be saved who had understood, and then rejected, justification by faith alone. In fact, Dr. Gerstner interpreted Scott’s becoming Catholic as evidence he had never been a Christian at all!

Instead of leaving the Protestant Church, [Scott] was leaving the lost world into which he was born — and from which he was never actually separated — for the false church of Rome. He has leapt from the frying pan into the fire, and only God can deliver him as a brand from the burning.6

Catholics read these words and think: what?

So, in Dr. Gerstner’s mind it’s justification by faith alone or nothing? Yes, that’s correct. Being in the Church of Rome is the same as being lost? Yes. He doesn’t believe Catholics are even Christians? No, he doesn’t. And there are many who don’t. And the ones who don’t tend to be the ones most serious about the Protestant doctrine of sola fide. And it’s because in their view the very Gospel of Jesus Christ is at stake in this dispute between the Protestant and Catholic views of justification.

In their thinking only two options exist: either we are justified by faith alone in the imputed righteousness of Christ, or we are attempting in some manner to earn salvation through our obedience.

If Christ’s perfect righteousness is credited to us, Protestants will argue then and only then is salvation entirely the work of God. Then and only then does God receive all the glory for the work of redemption. If, on the other hand, our obedience is in any sense a part of what is required, then salvation is partly God’s work and partly ours; we have contributed to our own salvation, and we have something in which to boast.

This is how serious Protestants think about this issue.

And because Catholics do see obedience as required, serious Protestants see Catholics as teaching what well-known Calvinist pastor and author John MacArthur refers to as “a damning system of works-righteousness.”7

Now, Catholics would likely scratch their heads at this. After all, Catholics know that salvation is the free gift of God and that even our good works are the fruit of God’s grace working within us. When Catholics walk forward at Mass to receive Communion, their hearts instinctively resonate with this prayer of St. Thomas Aquinas:

Almighty and ever-living God, I approach the sacrament of your only begotten Son, our Lord Jesus Christ. I come sick to the doctor of life, unclean to fountain of mercy, blind to the radiance of eternal light, and poor and needy to the Lord of heaven and earth.

Catholics know it is grace, from first to last!

But because Catholics believe that we must use our freedom to cooperate with God’s grace, that justification is a process and that the obedience of faith is a part of what is required of those who would take up their cross and follow Jesus and inherit eternal life — to many Protestants, Catholics are teaching “salvation by works.”

MacArthur writes:

The difference between Rome and the Reformers is not theological hair-splitting. A right understanding of justification by faith is the very foundation of the gospel. You cannot go wrong at this point without corrupting every other doctrine as well. And that is why every “different gospel” is under the eternal curse of God.8

Conclusion

It’s easy for me to describe this line of reasoning. I know it well. I was taught it as a new Christian. It was believed and taught at the Bible college and seminary I attended. For years my favorite theologians were men who believed and taught it, such as Luther, Calvin, the puritans John Owen, John Bunyan, and Jonathan Edwards. I also believed it and taught it. But, over time, I began to have questions.

Coming Soon: Luther: The Rest of the Story, Part IV

- Roland Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther, p. 65.

- Luther, Martin, The Freedom of the Christian, quoted in Msgr. Patrick F. O’Hare The Facts About Luther, p. 101.

- Bainton, p. 65.

- Paul Althaus, The Theology of Martin Luther, pp. 81, 85.

- Luther, Against the Spiritual Estate of the Pope and the Bishops Falsely So-Called, found in LW 39: 248-249.

- John Gerstner, Justification by Faith Alone, Ed. Don Kistler, p. 185.

- Ibid, p. 2.

- Ibid. p. 20.