“The world is charged with the grandeur of God…”

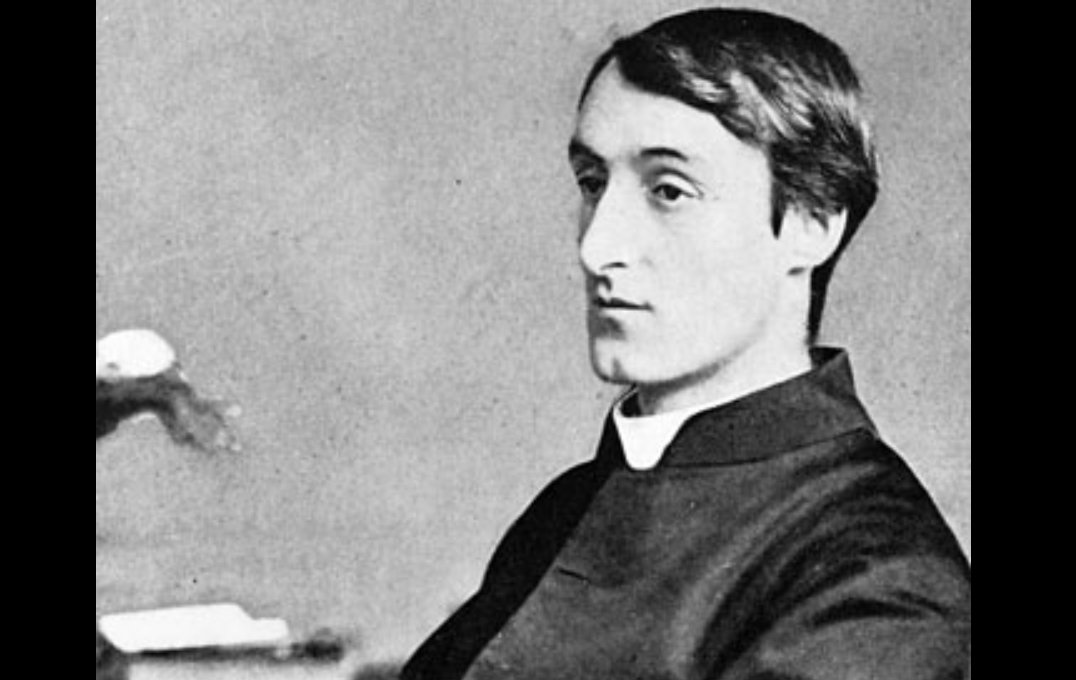

So begins God’s Grandeur, one of the most famous poems from 19th century English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose works did not begin to gain wide notoriety until after his death. And while his work is regarded as highly influential in the history of the Western literary tradition, his conversion to Catholicism and his vocation to the priesthood as a member of the Society of Jesus are not as widely known.

Hopkins was born into a prominent Anglican family in 1844, and several of his relatives were involved in various artistic pursuits, from the visual arts to music and poetry, as well as the study of languages. All of these interests were instilled in Hopkins from a young age and led him to pursue an education at Oxford. While there, he developed a friendship with Robert Bridges, who would go on to later become Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom. It was also during this time that he became more engaged with both ascetic practices and the pursuit of beauty. These questions began to lead him beyond his Anglican roots and deeper into the Catholic tradition.

This search for his true spiritual home finally came to a head when Hopkins decided to reach out to one of England’s most famous Catholic converts: St. John Henry Newman. Newman had entered the Catholic Church in 1845, a year after Hopkins was born, and was well known in England among Anglicans and Catholics alike by the time Hopkins was studying at Oxford. Hopkins was able to meet with Newman in person in 1866, and it was Newman himself who received Hopkins into the Church in October of that year.

Like many 19th century Anglican converts, the decision to become Catholic caused conflict and estrangement between Hopkins and his family, and also had an impact on his academic and professional trajectory. The employment question was initially resolved when Hopkins was offered a job at the Birmingham Oratory by Newman, and it was not long after taking that position that Gerard felt a strong call to religious life as a Jesuit. Having written poetry for years, he initially perceived there to be a conflict between his poetic interests and his religious vocation; in a moment of passion, he burned most of his poems, and didn’t write again for another seven years. This mix of artistic fervor, ascetic impulse, and melancholic swings would mark the trajectory of Hopkins’ entire adult life.

Over time, however, Hopkins began to see that there need be no conflict between his love of poetry and his priesthood, and he began to write poetry again. Only a few of these poems made it to print during his lifetime, as his innovative use of meter and imagery from nature were not always understood by editors and publishers. Unfortunately, by the time he had reached his 40’s, Hopkins found it more and more difficult to write, due to increasing difficulties with his health, and a nagging worry that pursuing publication of his poetry might lead to pride, which he constantly feared would be an impediment to his vocation as a Jesuit priest.

Hopkins died in 1889 at only 44 years of age, and it wasn’t until 1918 that his work received wider distribution and acclaim. His old friend Robert Bridges, who had been named Poet Laureate in 1913, decided to use his own influence to get some anthologies of Hopkins’ work published. In those years following World War I, the uniqueness of Hopkins’ style and the insights of his writing finally took hold with a wider audience, going on to influence such major 20th century poets as W.H. Auden and T.S. Eliot.

Hopkins was a complex and interesting figure; his struggles with both physical and mental health, especially toward the end of his life, reveal swings between wonder at God’s creation, and melancholy over the state of the world and his own soul. But through all of his poetry, a distinct sacramental worldview shines through. God is the Father of all, by whose hand all things are made, and whatever causes wonder ultimately points to him. As Hopkins writes in the closing line of his poem “Pied Beauty”:

“He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change: Praise him.”