For years, I’ve been fascinated with a little-known figure in American Church history: Father John Thayer (1758-1815). He served as chaplain to John Hancock during the American Revolution, was the first American born priest of Boston and missionary to Kentucky, and his 1798 Fourth of July sermon is included in the list of Great American Political Speeches. In my view, however, his most significant claim-to-fame is that he was the first American-born Protestant minister convert. He published the story of his conversion in 1787 (the first of its kind in American history) as An Account of the Conversion of the Reverend John Thayer, Formerly a Protestant Minister of Boston Written by Himself (available here).

His name appears in most history books covering the Catholic Church in America, but rarely with much detail, and often with a less than positive tone. One great American historian, Theodore Maynard, in his book The Story of American Catholicism, described Fr. Thayer as “A man of some ability, and no complaint could be brought about his morals. But he was ‘difficult,’ retaining much of the stern inflexibility of the Puritan minister.”1 Peter Guilday, in his The Life and Times of John Carroll, suggests that “Father Thayer was gifted with genius of no mediocre quality, and was a scholar as well as a wit; but, as one writer has expressed it [paraphrasing Maynard], ‘not a little of the uncompromising Puritan spirit clung to him to the end.’”2

It is true that Fr. Thayer’s bold, and apparently brash, convictions ruffled many feathers during the fourteen years he served as a Catholic priest in post-Revolutionary America. He particularly found himself embroiled in difficult conflicts during his final four years as a missionary in Kentucky, at a fledgling wilderness parish that has long had a reputation as a “troublesome parish.”3

Perhaps the biggest cause of his troubles, though, was that, while most post-Revolutionary American Catholic leaders were focused on helping the newly liberated Catholics become fully incorporated Americans, Thayer’s primary “mission” was to help his countrymen become Catholic. In Thayer’s published testimony, two years before he returned to America from Paris as an ordained Catholic priest, he expressed these convictions to the world:

This is the prevailing wish, this is the only desire of my heart, to extend as much as lies in my power, the dominion of the true faith, which is now my joy and comfort. I am ambitious of nothing more; for this purpose I desire to return to my own country, in hopes, notwithstanding my unworthiness, to be the instrument of the conversion of my countrymen; and such is my conviction of the truth of the Roman Catholic Church, and my gratitude for the signal grace of being called to the true faith, that I would willingly seal it with my blood, if God would grant me the favor, and I doubt not but he would enable me to do it.

Short of writing a lengthy biography, I would like to suggest for now that there is something very important we can learn from the experience of this first American-born Protestant clergy convert. I suggest this with the hindsight of 200 years, as well as the CHNetwork’s eighteen years of working with other American Protestant clergy inquirers and converts. Certainly, there is a long list of blessings that accrued to American Catholicism due to Thayer’s priestly ministry in post-Revolutionary America. He celebrated the first Masses in many New England towns, including Salem, MA, and his skillful and charitable apologetic publications in the Boston press were the first of their kind in American history. He also fought significant battles that eventually opened doors for successful Catholic ministries in Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, and Kentucky.

However, again with hindsight, is it possible that the biggest cause of his problems was not because of his “mercurial nature,”4 or because he failed to leave his enthusiasm at the door, but rather simply because he became a priest rather than remaining a layman?

Now I generally do not think it appropriate for any of us to entertain the spurious question, “I wonder whether my life would have been ‘better’ if I hadn’t _______ or if I had _______?” Opening this unanswerable Pandora’s Box is a subtle way of denying or questioning the constant yet invisible Hand of God in our lives. However, without denying this guiding plan of God, can we not pose the question whether his mission might have been more effectively accomplished if he had returned to America a Catholic layman?

Like so many today, most Protestants as well as Catholics in Thayer’s time assumed that the only way to truly serve the Lord was in some kind of full-time, Church-supported, clerical ministry. Those around Thayer after his conversion assumed that the only way he could now serve the Church in America was as an ordained priest, not as a layman. What is interesting, though, is that it appears that this was not his assumption: rather, it seems that he was resolved to return to America, to fulfill his evangelistic convictions, as a lay missionary.

In 1781, with the American Revolution winding down, 23 year old John Thayer sailed to Europe to expand his education, with the apparent goal of returning to teach at Harvard College. There seems to be no evidence that his ambition was to continue as a Congregational minister. Then unexpectedly, after being greatly moved by the miracles associated with the death of the saint mendicant Benedict Joseph LaBré, Thayer was received into the Catholic Church in Rome in May, 1783. While in Rome, he met with Pope Pius VI and many cardinals and priests who received him with open arms and enthusiasm. With their encouragement, he returned to Paris where, with the pope’s letter of introduction, he made contact with the Archbishop of Paris, the Papal Nuncio, and other Church hierarchy, as well as American Ambassador Benjamin Franklin.

The news of the conversion of this former Protestant minister spread throughout Europe. Since he appeared so chummy with the French, some of the Catholic clergy in England, still suffering under penal oppression, were a bit suspicious of his loyalties. A year after Thayer’s conversion, Father Charles Plowden, a suppressed-Jesuit priest living at Weld castle in southern England, wrote his long-time fellow ex-Jesuit friend John Carroll news about his fellow American:

I am informed that Mr. Thayer the Bostonian convert mentioned in my last is highly commended by the French Archbishop at Paris, especially Pere Mat, whom you remember at Bologna by the name of Abbe Le Bon. Mr. Thayer is said to have no inclination to the Eccles. state, & to have extinguished his scheme of carrying missioners to Boston….” 5

Fr. Plowden is not passing along first hand information, so the accuracy of his details may be slanted, possibly because he is convinced Thayer is in cahoots with the detested French, and therefore cannot be trusted (more evidence of this prejudice abounds in this and other letters). His mention of Thayer’s “scheme of carrying missioners to Boston,” however, is an important admission, for it is the first recorded mention of what will remain Fr. Thayer’s primary life-long ambition: to bring priests and nuns to America to promote the Catholic Faith to his countrymen.

It may be that after his meetings with Franklin and the Nuncio in January 1784, Thayer was feeling discouraged and impatient. His understanding of Catholic missions was only a few months old, while his life-long experience had been with independent missionaries, ordained, sent forth, and supported under the authority of local congregations. From childhood, Thayer certainly would have heard the stories of John Eliot, the Puritan Apostle to the Indians, who had been instrumental in the conversion of the Massachusett “praying” Indians a hundred years before Thayer’s birth. The model of Eliot’s bold independence to spread the Gospel may have planted the seed, possibly from childhood, of what a missionary was like.

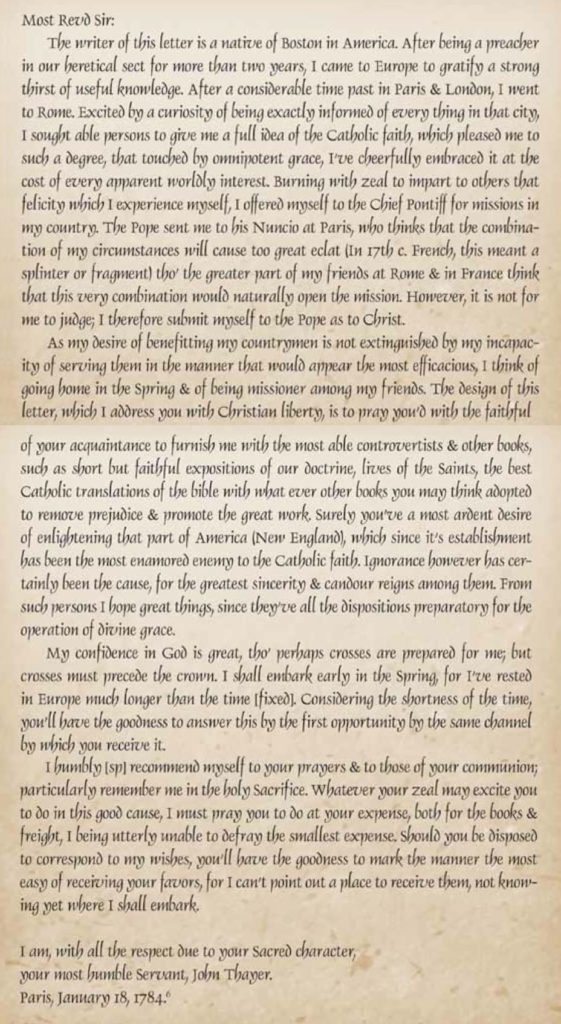

It may have been out of his discouragement, therefore, that Thayer set aside as unnecessary any idea of seeking ordination to the priesthood as a qualification for returning to America as a missionary. Plowden alludes to this, but, more significantly, we catch a glimpse of this in an important letter Thayer himself wrote. The letter was written to the Vicar Apostolate of London, James Talbot, not long after Thayer’s meetings with Franklin and the Papal Nuncio. This is the first known extant letter in Thayer’s hand, and the first recorded instance of Thayer’s own description of his conversion and dreams for his return to America, penned three years before the publication of his Account.

Prior to the American Revolution, all Catholics in the British Colonies were under the authority of the Vicar Apostolic of London. As a result of American independence, American Catholics were like orphans, without anyone to look to for leadership, other than directly to Rome. A similar problem arose for American members of the Anglican Church of England. They solved their dilemma, however, by forming their own new American-based church called the Episcopal Church of America, loyal to the Archbishop of Canterbury, yet independent. Faithful American Catholics, of course, could not nor would even consider such a notion. This would become a hotly debated issue amongst American Catholics, and even involved Benjamin Franklin and the American Congress.

For the new convert John Thayer, this would have been an issue to which he likely was oblivious. Before becoming a Catholic, as a life-long New Englander who had never met a Catholic or ever given the state of American Catholics the slightest thought, the issue most likely never crossed his mind. Now as a neophyte Catholic in Paris, he was mostly out of the loop of any of these discussions. Consequently, it is understandable that as he contemplated his future, he may have presumed that, until otherwise decided by Rome, the American mission was still under Vicar Apostolic Talbot.

Of all the archival primary source documents connected to the life of John Thayer, I believe that this letter to the Vicar Apostolic of London is the most important and revealing:

So much of what this new convert reveals in this letter connects with his future, as well as the struggles of hundreds of clergy converts of our own day. When he confesses to the Vicar Apostolic that “I’ve cheerfully embraced it at the cost of every apparent worldly interest,” he is expressing in a nutshell what every clergy convert has always had to face when converting from the Protestant ministry to the Catholic Church: potential loss of vocation, abandonment of calling, and rejection by family, friends, and colleagues. It’s likely that Thayer had never met or even heard of another Protestant clergyman converting to Catholicism. Certainly there were some, primarily Anglican clergy. In fact, one of the Catholic priests arriving on the Ark and the Dove to establish the Maryland colony in 1654 was a former Anglican priest, but it’s highly unlikely that Thayer ever heard of this. As far as we know, he was the first American-born Protestant clergyman to convert. All this to say that he had no previous models to follow, and though the Church hierarchy had dealt with Anglican priest converts, they had never faced the conversion of an American Puritan minister.

Since John Thayer was not married, he would not have been barred from consideration for the priesthood. As a result of the modern Pastoral Provision granted in the 1980s and more recently the Anglican Ordinariate, today’s married Anglican/Episcopalian clergy converts have the possibility of dispensation from the requirements of celibacy, but in Thayer’s day this would not have been possible. Nonetheless, given all the other presumptions and prejudices of the time, it’s understandable that Thayer assumed that his conversion could mean the loss of everything he knew or dreamt of doing.

When he states that he was offering himself “to the Chief Pontiff for missions in my country,” we hear a clear and precise description of what he now believed God was calling him to do: not a call to the priesthood in general or to the diocesan/parish priesthood in particular, where his focus would be the sacramental ministry to Catholics, but rather to the missions where his focus would be the evangelistic outreach to his non-Catholic countrymen. This he states when he assures the Vicar Apostolic that “my desire of benefitting my countrymen is not extinguished by my incapacity of serving them in the manner that would appear the most efficacious.” Since he essentially knew of no American community of needy Catholics, especially in New England, his primary vision was that of “being missioner among my friends,” bringing to them for the first time the truth of the Catholic Faith. He believed that “Ignorance … has certainly been the cause” of their life-long separation from the Church, not lack of faith or commitment, “for the greatest sincerity & candour reigns among them.” As a result, he is anxious and fearlessly ready to start his mission, for from “such persons I hope great things, since they’ve all the dispositions preparatory for the operation of divine grace.”

Nor was there the option of his willingness to present himself freely to an American bishop, to serve in whatever capacity was needed, for there was not yet an American bishop. Father John Carroll would not be appointed by Rome as the Prefect Apostolic for another year, and frankly there would not have been reason for any mention of Carroll’s name in any of Thayer’s circles.

Consequently, there seems to have been no reason for Thayer to delay his return for further study or ordination to the priesthood. He was thinking “of going home in the Spring” to be essentially a lay “missioner among my friends.” He does not seem to have been even thinking of starting a local Catholic church, or especially of being placed wherever needed at the various scattered Catholic settlements in the south or west—which is what happened and proved to be outside his skills and temperament. No, he saw himself as a lay evangelist ready to “embark early in the Spring, for I’ve rested in Europe much longer than the time [fixed].”

There is also no indication that he was asking for or expecting any kind of financial support. He was only asking for a donation of theological and devotional books that he could use and distribute in his missionary efforts (which Vicar Apostolic Talbot eventually did send to Boston for Thayer’s use).

These are all key points to remember when anyone criticizes what happened to Fr. Thayer after he arrived in America in 1790, an ordained Catholic priest. What he will prove to be keenly effective at is exactly what, at this point, he believed God was calling him to do, while what he will be expected and commanded to do by the newly appointed Bishop Carroll will be the opposite—and as a parish priest, especially in rural or wilderness America, he will utterly and constantly fail, leading to discouragement, depression, and even a suspension of his faculties. Even when, in his letters to his Superior, he clearly admitted to his strengths and weaknesses, asking not to be placed in parish leadership, he, nonetheless, was given only parish assignments, for parish priests were essentially the only thing that Bishop Carroll needed given the needs of the American Catholic diaspora. Unfortunately, Fr. Thayer in many ways failed as a parish priest, and to this day is remembered not for his successes, but for his failures.

And it was as if he already knew that this would happen, for to Vicar Apostolic Talbot of London he professed, “My confidence in God is great, tho’ perhaps crosses are prepared for me; but crosses must precede the crown.” Indeed, from the time he eventually set foot in America in 1790 to the moment he boarded a ship fourteen years later to return to England, a broken priest, his life was one continuous cross. All of this, however, he was willing to face because he was “burning with zeal to impart to others that felicity which I experience myself.” Even after his failures in America, though, he returned to Europe to raise money to recruit and fund priests and religious to return to the American mission. After receiving back his faculties, he spent the remainder of his days a humble priest, in imitation of his patron, Benedict Joseph Labre. He died in 1815, with the reputation of a holy priest in the model of the Cure of Ars.

There is much that we can learn today from the experience of this “patron” of American clergy converts, but maybe most significantly, I believe that non-Catholic clergy inquirers and converts need to think very carefully as to whether the most obvious trajectory for their vocations is the Catholic priesthood. Instead, I believe they need to begin by focusing singularly on becoming faithful and holy Catholic lay men and women.

Jesus once told His hand-chosen Apostles, “When you are invited by any one to a marriage feast, do not sit down in a place of honor, lest a more eminent man than you be invited by him; and he who invited you both will come and say to you, ‘Give place to this man,’ and then you will begin with shame to take the lowest place. But when you are invited, go and sit in the lowest place, so that when your host comes he may say to you, ‘Friend, go up higher’; then you will be honored in the presence of all who sit at table with you. For every one who exalts himself will be humbled, and he who humbles himself will be exalted” (Luke 14: 7-11). His Apostles would one day become the leaders of the fledgeling Church. Yet, Jesus exhorted them to focus first on humbly pursuing holiness, receiving the Kingdom as children.

We become children in the family of God—the Body of Christ, the Church—through Baptism. Our primary calling is to become faithful, humble, submissive followers of Christ. If we come into the Catholic Church with a life-long non-Catholic heritage, like the life-long Puritan heritage of John Thayer, it takes a long-long time, sometimes many years, to fully understand what it means to live as a faithful Catholic—and to identify and then correct assumptions and eradicate habits from our past that may continue to plague us long into the future.

For this reason, I want to extend a caution: clergy inquirers and converts need to be careful not to presume that their Protestant training and ordinations now entitle them to automatic consideration for Catholic ministry leadership. Their resumes may outline what they were able to do within a Protestant context, but it may not necessarily translate to what they can do in a Catholic context. It is amazing to what extent these two contexts are different!

Instead, clergy converts need to begin by recognizing that the vocation of a Catholic laymen is not a step down, but, by virtue of the sacrament of Confirmation, a step up! By humbly and willingly accepting the high call to be a Catholic laymen, convert clergy can then prove, in humility and love, whatever skills they have brought with them, so that, if God so leads, someone in parish or diocesan leadership may come to them, and invite them into leadership: “Friend, go up higher.”

If he could, what might Father Thayer say, again with hindsight, to modern non-Catholic clergy inquirers and converts? Given what I’ve learned through my study of the successes and failures of his life, I believe he might give the same advice that Saint Paul gave to his fledging associate bishop, Saint Titus: “Remind them to be submissive to rulers and authorities, to be obedient, to be ready for any honest work, to speak evil of no one, to avoid quarreling, to be gentle, and to show perfect courtesy toward all men” (Titus 3:1-2). I also believe he would second the advice of his Master: “When you are invited, go and sit in the lowest place.” There is not a one of us who can’t use a double dose of humility.