When I was eight years old, my best friend informed me that I would be going to hell since I had not yet been baptized. My best friend had been raised in a devout Missouri Synod Lutheran home, and he knew well enough that he belonged to Christ through baptism. I, on the other hand, had not been raised in any Christian tradition, nor had I been baptized. It seemed, then, that I would not be saved, nor could I be saved. Baptism remained for me something mysterious and unattainable.

My family was not Christian, but was generally virtuous. My mother forbade certain shows and movies as inappropriate for little ones. Lying and stealing were condemned and traditional values upheld.

Nevertheless, religion was lacking. My maternal grandfather had abandoned his childhood Lutheran faith when the pastor publicly rebuked him regarding his tithe. My maternal grandmother had left her childhood Catholic Faith when she witnessed a priest scold a pregnant friend who turned to the Church for help with a baby conceived out of wedlock. My paternal grandfather had died while my father was a boy, and as a result, my father did not receive any religious education.

As a result, both my parents had been spiritual orphans. As my Lutheran friend observed, then, I had not been baptized and was heading toward eternal damnation.

Salvation through Scripture

All this changed when I was twelve years old. I received a baseball autograph from the catcher of the Texas Rangers, Darryl Porter. He had signed his name and written under it: “Rom 10:9.”

I was eager to discover his secret message for me. When I found out that this codeword was a Bible verse, I searched for a Bible. After some time, I found Romans chapter 10, verse 9, and my heart filled with joy as I read these words:

“If you confess with your mouth, ‘Jesus is Lord,’ and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.”

At last, I thought, I’ve discovered a way to be saved!

Immediately I said aloud, “Jesus is Lord” (since the Scriptures instructed “with your mouth”). I uttered my first prayer to God, confessing that God raised Jesus Christ from the dead. I didn’t know what these words meant, but I knew that I wanted to be saved and that I’d discovered a way of salvation without the apparent prerequisite of baptism.

Soon I was eager to learn more about Christianity, so I began to ask questions about “religion.” I wanted to know about Baptists, Lutherans, Methodists, and Catholics. I discovered the meaning behind holidays like Christmas and Easter.

Before long our whole family was attending services together at the nearby church, a Methodist congregation. During this time I felt that God was calling me to become a pastor.

One day a well-meaning evangelical Protestant camp counselor told me that I must read the Holy Scriptures every day, because the Antichrist would soon arrive and confiscate every copy of the Holy Bible remaining on earth! In these days of tribulation, he explained, the only Scriptures we would possess would be those we hid in our hearts through memorization. As a sixteen-year-old looking for spiritual direction, I took his admonition seriously. In the next two years, I read the entire Bible from Genesis to Revelation three times consecutively.

In time I discovered that there were “liberal” and “conservative” churches. As it was explained to me, “liberal” churches follow reason, and “conservative” churches follow Scripture. I certainly wanted to be one of the faithful Christians who followed Scripture.

I visited a charismatic congregation and was impressed by their so-called “altar call.” At the end of every sermon, the pastor would ask all present to close their eyes and bow their heads. He next addressed those who were not Christians or who needed to recommit their lives to Christ. Then he would call them forward.

These penitents often cried while the music roared. I found this all very impressive. But after about three months, I noticed that the same people “got saved” week after week. The routine increasingly appeared formulaic. I desired something deeper.

John Paul II: The Antichrist?

When I later attended Texas A&M University, I majored in philosophy and minored in Greek and Latin. I gave up on the charismatics and looked for something more. There I encountered a “Bible Church” and was delighted to find a congregation that was biblical, conservative, and balanced. I became involved in Campus Crusade for Christ, went on a summer missionary trip to China, and always tried to share my faith with those who did not know Christ.

During this time I became fiercely anti-Catholic and convinced that Catholics were not “saved.” Whenever I asked a Catholic whether he knew Jesus Christ as his “personal Lord and Savior,” I received only blank stares or stuttered replies. From my evangelical Protestant point of view, Catholics wore crucifixes, but they did not know the crucified Lord personally.

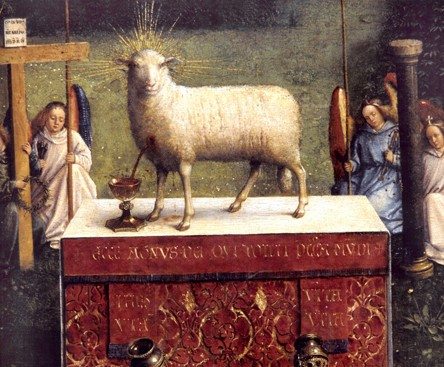

As I learned more about Catholics, I found that they were seemingly obsessed with the “Eucharist” (a new term for me). I soon discovered, to my horror, that they worshiped the Eucharist as if it were Christ Himself! I also learned that they were united in their love and appreciation for “Pope John Paul the Second.”

My knowledge of the Catholic Faith at that point consisted only of these three facts: 1) Catholics do not know what “faith in Christ means,” 2) Catholics worship bread, 3) Catholics love Pope John Paul II.

Like the once-Anglican John Henry Cardinal Newman, I jumped to the conclusion that the Catholic Church was the Beast of the Apocalypse and that the Pope was the Antichrist. My thinking went like this: “If the Pope loves Jesus Christ, then he would certainly teach his people to have faith in Christ — to love Him always and to draw near to Him — not to worship bread, nor ignore the Scriptures.”

My mind was made up. I agreed with a remark the Puritan writer Richard Baxter once made: “If the pope be not anti-Christ, he hath the ill-luck to appear so much like him.” Here, I thought, was a man who fit the description of the Devil’s allies in the Apocalypse.

He wore gold and jewels, and he surrounded himself with men donning scarlet and purple (see Rev 17:4). Crowds hailed him. He addressed the United Nations. Presidents and prime ministers visited him and kissed his ring. He held up bread to be worshipped. For me, John Paul II had to be the Antichrist.

Faith and reason come together

Having established that the Catholic Church is “antichristian,” I soon discovered a theological system that would further confirm my suspicions about it. Among my evangelical friends were those who favored “Reformed” theology. These men often met together to discuss John Calvin and others in the Reformed theological tradition.

I purchased my own copy of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion and began to read. For the first time in my life, I discovered a system of Christianity that claimed to be intellectually coherent and faithful to Scripture. I had initially believed that faith stood contrary to reason, just as “conservative Christianity” stood contrary to “liberal Christianity.” At last, I learned that faith and reason complement one another — that faith perfects reason. The Reformed version of Protestantism was conservative, anti-Catholic, and intellectually satisfying for me as I sought to find my way through college as a philosophy major.

As I read Calvin and other Reformed theologians, I discovered four things. First, I learned that sacraments are important. Calvin seemed to take the sacraments more seriously that I presumed possible. He made a strong case for infant baptism and weekly communion. Although Calvin’s understanding of the sacraments was seriously erroneous in many ways, I discerned through reading him that the sacraments are the divinely appointed means of grace.

Second, I came to see how God ordered the history of human redemption covenantally. Salvation history was important, and the New Testament stood in continuity with the Old Testament. Having rejected dispensationalism, I began to read the Old Testament in light of the New.

Third, I discovered the Fathers of the Church, especially Augustine, John Chrysostom, and Ambrose. Their teaching opened up many new doors of understanding for me.

Finally, I concluded that Catholic teaching was even worse than I had previously imagined. The Protestant Reformers revealed further “Romanist errors” regarding justification, authority, Eucharistic sacrifice, and the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Despite my acquired prejudice against “Romanism,” my introduction to the Church fathers eventually led me to read them in their own words. As I read the Fathers, I discovered that they were liturgical, and that the Eucharist held the central place in their worship. I also observed the ancient threefold hierarchy of bishop, priest, and deacon — which in turn led to an appreciation for apostolic succession.

I still held to the traditional Protestant distinctions of “justification by faith alone” and “Scripture alone.” But I was becoming progressively sacramental. I enrolled in the nation’s foremost Reformed seminary, Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. If the faculty of Westminster could not cure me of my growing appreciation for the sacraments, I would do the “reasonable” thing: I would follow the road to Canterbury and become an Anglican!

Becoming an Anglican priest

At this time I met my wife, Joy. She had been raised Baptist but had also become a “sacramental Presbyterian.” We were both members of the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA).

On our first date she mentioned the Eucharist. On the second date, she brought up apostolic succession. I was convinced that she was the woman for me!

Here was a beautiful college girl asking the same questions that I had been asking. A year later, we were engaged.

Westminster Seminary was a wonderful place for us, and we grew in our faith. Yet it became increasingly clear to us that Reformed and Presbyterian churches were too “Protestant” for us and that the Catholic Church was, well, too “Catholic.” So we followed the via media and became Anglicans.

I felt an initial joy and excitement as I began to pray the Divine Office throughout the day, attend daily Communion, and receive spiritual direction from an elderly Episcopal priest. Our first child, Gabriel, was baptized in the Anglican tradition. Before long we were in seminary again — this time at Nashotah House Theological Seminary in Wisconsin.

Nashotah House bears a reputation as the “Anglo-Catholic” seminary of the Episcopal Church. “Anglo-Catholicism” refers to a movement within Anglicanism that leans toward a more Catholic understanding of the Anglican tradition, especially the Anglican priesthood. My Episcopal bishop explained to me that he was satisfied with my theological education, but that he wanted me to become more Catholic liturgically and devotionally. He desired for me to learn how to chant, baptize a baby, celebrate funerals, cense an altar, and hear confessions. I was to become not merely a “minister” but a “priest.”

Now that I no longer maintained that the Catholic Church was entirely evil, I began to experience what some have called “Catholic angst.” In other words, now that I was enthusiastically adopting more and more of the Catholic tradition, I began to feel some anxiety as I felt drawn in some ways to the Catholic Church. As G.K. Chesterton once observed, “The moment men cease to pull against the Catholic Church, they feel a tug towards it.”

My time at Nashotah House exposed me to Catholic piety in a tangible way. The Angelus bells were rung morning, noon, and evening. We prayed and chanted the cycle of the Breviary from our hand-carved choir stalls — stalls similar to those found in medieval monasteries.

I wore a black cassock every day to prayers and classes, and I removed it only after the seminary celebrated Vespers toward the end of the day. Priests were available for confessions. The Anglican Eucharist was celebrated every morning — sometimes with the priest facing ad orientem as in the old Latin Mass. Eucharistic adoration was encouraged.

On some days I would wander off into the woods in my cassock, read devotional literature, and pray in silence. I often read works by St. Basil the Great and Saint Gregory Nazianzus during these times. Now I look back on those days as essential preparation for what would eventually become a difficult and rocky time.

The Pope Is Dead!

On April 2, 2005, I heard the news that Pope John Paul II had died. As I came into our home, my wife could tell that something was wrong. I recited, almost as if I were speaking in tongues, “Papa mortuus est,” which in Latin means, “The Pope is dead.”

She and I began to cry. Although I had once labeled John Paul II as the “Antichrist,” I now revered him as a father. It was as though my father had died, and I had never known him. Everyone else at the seminary as well knew that a great man had died.

Deeply moved by the passing of John Paul II, my wife and I decided that we would attend Holy Mass at the local Catholic parish to show our respects to the Pope and perhaps hear a moving homily in tribute to the man people were already calling “John Paul the Great.” The following Sunday, we arrived at a modern-looking building and entered for Mass.

As it turned out, the Catholic priest said precious little about John Paul II. Instead, he spoke about how St. Peter was not the true author of either 1 Peter or 2 Peter. Moreover, during the consecration prayer he had people come forward and stand around the altar with him. The priest proceeded to recite a Eucharistic prayer that he had composed — a prayer that rhymed. I remember the words at the consecration going something like this:

“On the night before he was dead,

Jesus took into his hands bread.”

Joy and I were horrified. Not only was this terrible poetry, it seemed sacrilegious and contrary to the life and message of John Paul II — a message of perfect obedience to Christ. We loved the Catholic John Paul II. We were not ready for this local Catholic parish with its liberal priests and hokey rhymes.

A rabbi points me to Rome

A few weeks later, I was ordained as an Anglican deacon. Soon afterward I was ordained to the Anglican priesthood. It was a time of great joy and excitement.

I was assigned to be the curate at Saint Andrew’s Episcopal Church in downtown Fort Worth, Texas. I felt perfectly fulfilled as I began to preach, celebrate the sacraments, and exercise pastoral care. I was especially excited one day to make my first hospital visit as a clergyman.

The pastor of the parish gave me the name of a woman who was about to receive an operation at the local hospital and asked me to visit her. Little did I know that by the end of that day, I would have had a conversation with a rabbi that would set my entire life going in a new direction.

I drove to the hospital, and with a prayer book under my arm, I obtained my “clergy parking” tags, washed my hands, and went upstairs to the waiting room. It was packed with people waiting for their loved ones to return from surgery. I went to the desk, smiled at the receptionist, and said, “My name is Father Taylor Marshall and I’m here to see Joanna Smith before she goes into surgery.”

The receptionist’s fingernails stopped clicking on the keyboard. “Great. You can just go on back there and see her.”

I turned around and saw the two swinging medical doors.

“Through there?”

“Yes, Father. Just go on in. Mrs. Smith is already with the anesthesiologist.”

It was clear that she believed that I had done this before, but it was my first time. As I came to the doors, I pushed the button and they swung open. I walked forward and they closed behind me. I entered into a large room with eight beds. A nurse smiled at me.

“Pardon me. Can I help you?”

“Yes, I’m hear to see Joanna Smith.”

“She’s over there in bed #1. The anesthesiologist has already been here. She’s probably already asleep.”

“That’s okay,” I said. “I’d still like to pray for her.”

The nurse had no problems with this proposal and left me alone in the room.

I walked over to bed #1 and saw a woman already fast asleep in her hospital gown. I opened my copy of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, where a gold ribbon marked the section entitled “The Order for the Visitation of the Sick.” I then gently laid my right hand on the arm of the sleeping woman.

Her eyes flung open with an expression of fright. “Who are you?” she said. The anesthesia had not yet begun its work.

I was just as startled. I pulled my hand away from her arm. “Excuse me. My name is Father Taylor. I’m here to pray with you before you go into surgery.”

She took one look at my clerical collar and cried out, “But I’m Jewish!”

“Oh, I’m sorry. I must have the wrong bed. I was looking for someone named Joanna Smith.”

“That’s me. I am Joanna Smith.” She obviously had no idea why a Christian minister was bending over her bed with a prayer book in his hand.

I paused and thought to myself: Is this some sort of joke that older priests play on new priests? The pastor sends me off on my first hospital call with all sorts of sound advice, but neglects to tell me that the lady is Jewish! I collected myself.

“Well, would you like me to pray for you before you go into surgery?” I asked.

“Oh, I would love that. Thank you so much.”

I placed my right hand once again on her arm and prayed that she might be kept safe during her procedure. I left her with some words of comfort as her eyes became heavy and she fell asleep.

When I returned into the waiting room, I saw a bearded rabbi. So the priest (that’s me) walked up to the rabbi and said, “Are you here to see Joanna Smith?”

The rabbi answered, “Yes. As a matter of fact I am.”

“Go through those doors and follow the hallway to the left. Bed #1. She’s about to go under for surgery.”

Looking into the perplexed eyes of the rabbi, I could see what he was thinking: Why does this priest know all this about Joanna? He thanked me and disappeared behind the automated doors with a push of a button.

Just after that, I recognized someone in the waiting room. It was Mr. Smith from St. Andrew’s. Now I understood why I had been sent to pray with a Jewish woman: She was married to an Episcopalian.

Up until now, I hadn’t known that his wife was Jewish. He was nervous about her surgery, and we talked for a while until the rabbi returned to the waiting room. Mr. Smith introduced us to one another, and I recall a brief conversation with the rabbi about liturgy and the importance of chant.

Then the rabbi asked Mr. Smith a very unusual question. “What is the Hebrew name of Joanna’s mother?”

The husband thought about it for a moment. “Gee, I don’t know. Why do you ask?”

“Well, I was going to ask Joanna the name of her mother, but she was already asleep by the time I found her.”

“Why would you need to know her mother’s name?” her husband asked.

The rabbi explained, “We Jews believe that if someone is suffering and we invoke his or her mother’s name in prayer, then God will be more merciful in granting your intercession for that person.”

My first reaction was to dismiss the statement as superstition. However, as I let the rabbi’s answer sink into my soul, I realized the profundity of his belief. This rabbi believed that God was especially merciful when a mother was invoked for the sake of her child.

As an Anglican priest trained in the Anglo-Catholic tradition, I had a budding devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and I immediately realized the implications. I believed that Mary was important, because she was truly the mother of our Lord Jesus Christ and therefore the Mother of God. God had chosen this human woman to be the pure virginal vessel of His Incarnate Son.

If Jews believed that invoking the mother of someone caused God to be more gracious in answering an intercession, then wouldn’t the name of Mary be worth invoking? Didn’t her Son, Jesus Christ, become the Suffering Servant in order to redeem us?

Even more, Mary wasn’t just any ordinary mother. She was the only person ever created who could speak to God the Father and refer to “our Son.”

That’s when it hit me. Catholic devotion to Mary is not only based on sound Christological arguments. Marian piety is not only Patristic. The Church reveres and invokes the Blessed Mother because it inherited the Jewish custom of showing profound reverence for the spiritual role of the mother of a family.

Here was a surprising confirmation that Catholic customs are rooted in a Jewish understanding of God and His People. I began to study Catholic traditions in light of the Old Testament and found that the hermeneutic of continuity (recently expressed in Pope Benedict XVI’s book Jesus of Nazareth) unveils an authentic Christianity that is distinctly Catholic.

My Canterbury Trail to Rome

Joy and I decided to fly to Rome before we did anything drastic. While in Rome, we had the opportunity to attend Holy Mass with Pope Benedict XVI. I stood there in Saint Peter’s Basilica in my Anglican cassock — knowing that I could not go forward and receive the Holy Eucharist. Everything in my soul desired to be in communion with Pope Benedict XVI. In that moment, I knew that I was in schism and out of communion with Christ’s divinely instituted Church.

The next day I met Monsignor James Conley, who immediately introduced me to William Cardinal Baum. While the Cardinal sat with me alone in his apartment overlooking St. Peter’s Square, he began to question me about a number of doctrines: sacraments, Mary, the Eucharist, the priesthood, the Church, the liturgy, and more. At the end of this inquisition, he closed his eyes and let out a deep sigh.

“My son,” he said to me, “you are a Catholic. It is time for you to come home.”

He encouraged me and prayed with me. He even gave me a rosary that had once belonged to Pope Benedict XVI. We prayed together in his private chapel before the Holy Eucharist — the Lord Jesus Christ. My path was now clear. I would become a Catholic no matter how much it would hurt, no matter how much it would cost.

When we returned home from Rome, I immediately went to see Bishop Kevin Vann of the Catholic diocese of Fort Worth. He received me warmly and became my true father in Christ. Three months later, I renounced the priestly ministry that I had received in the Episcopal Church in preparation for entering the Catholic Church.

The Episcopal Church possessed many ancient Christian practices. But I came to see that the Anglican schism of the sixteenth century, and the Protestant Reformation in general, did not reflect the original trajectory of the New Testament. Primarily, I saw that the Church is the Body of Christ and the temple of the people of God.

In the Old Testament, the people of Israel were not free to create a “new Israel” or form a new denomination of “Reformed Israelites.” No matter how corrupt the priests and kings of Judah might have become, the covenant of God remained in effect. I saw that the Reformation was generally a rejection of a united, visible Church — a notion taken for granted in the Book of Acts and especially in the writings of St. Paul.

Bishop Vann received our family into full communion with the Catholic Church on May 23, 2006. It was of course difficult for me to lay down the clerical collar. Nevertheless, I became a Catholic because I realized that unlike the Catholic Church, the Episcopal denomination could not trace its doctrine, liturgy, customs, and morality back to origins with a first-century rabbi named Jesus who roamed the Holy Land with a band of Jewish disciples.

As a Catholic Christian, I can now say with the Apostle Paul (who was once Rabbi Saul) that I “share the faith of Abraham, for he is the father of us all” (Rom 4:16).

When I recall how the Holy Spirit worked in my heart long ago, when I uttered a meager prayer based on a baseball autograph, I cannot help but wonder at the Divine Mercy of God. He is calling us all to Himself, and He uses a variety of means.

I still recite Romans 10:9 and say with my mouth, “Jesus is Lord.” However, now I am able to confess this mystery while I stand upon “the pillar and bulwark of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15).