What does it mean to be a man? What is the key to happiness and fulfillment? I’ve always thought the ancient Greek philosophers were really onto something with their answer — the complete and happy man has a sound mind in a sound body.

Before I knew about those Greeks, my childhood embodiment of such a man came straight from my television set. Here was a man more powerful than a speeding locomotive and able to leap tall buildings in a single bound, yet totally devoted to “Truth, Justice, and the American Way.” My early childhood fascination with Superman, you see, led me later to the Man of Steel’s ancient Greek prototypes — to Odysseus and Achilles, and most especially, to the mighty Hercules himself.

Now there was a model for a sound body — a mental image to fuel my fires as I prepared for bodybuilding and power lifting competitions in my teens. And as far as the mind goes, I discovered Aristotle, the Father of Logic, around that time. Social scientist Charles Murray, in his book Human Accomplishment, ranks Aristotle as numero uno in overall human achievement! It seemed I had found my ultimate model for excellence of mind.

By my teens I’m pretty much set in my ways with my models for manhood and happiness, but for a brief foray into intense Christianity. When I was about 15 and had started giving my abstract thinking abilities a little exercise, it occurred to me that if the lessons of my Christian (Roman Catholic) upbringing were true, then nothing in the universe was more important, and it was time to truly start living by the faith.

I was raised Catholic after all. We went to Mass every Sunday, and my brother and sister and I had always gone to Catholic schools. We were taught by wonderful Dominican sisters. I hesitate to admit that we often called them “penguins” because of their long black-and-white habits, since I have in later times grown so impressed by religious who openly wear their devotion to Christ “on their sleeves” — and everywhere else. From those early years at home and school, I gleaned a strong sense of morality, of right and wrong, and a respect for the intellect and self-discipline.

Still, I cannot say that I learned a great deal about the particulars of the Catholic Faith. At home we really didn’t talk much at all about Christ or the Church. As I have mentioned, though, at around age 15, I had somewhat of a conversion experience, triggered by that intellectual “Aha!” regarding the ultimate importance of Christ. My only really devout Christian friends at that time were not Catholic, though. One had converted away from Catholicism, but most had long been members of one or two local non-denominational or Pentecostal churches. I attended services with them with some profit. Many of these people’s lives had been turned around by their devotion to Christ. Some, I found, did not consider Catholics true Christians, but even in my state of relative ignorance of my own faith, I realized that we had Christ, too, and I did not abandon Catholicism for any form of separated Christianity. No, I ran into trouble elsewhere — within the musty pages of old philosophy books.

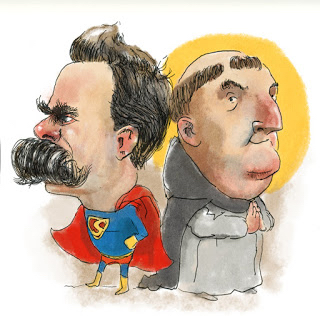

Always a bit of a bookworm, my reading took me deeper into philosophy. An old saying goes, “a little philosophy leads to atheism,” and by age 18 I had been so led. I immersed myself in the writings of Voltaire, Nietzsche, (complete with his own, yet quite different, conception of the “superman”), of Bertrand Russell, and especially of Ayn Rand, since she described her philosophy of Objectivism as the natural outgrowth of Aristotle’s writings. All of them (excepting Aristotle) viewed the idea of God as unreasonable and unnecessary, and at that point in my life, reason became my god.

Always a bit of a bookworm, my reading took me deeper into philosophy. An old saying goes, “a little philosophy leads to atheism,” and by age 18 I had been so led. I immersed myself in the writings of Voltaire, Nietzsche, (complete with his own, yet quite different, conception of the “superman”), of Bertrand Russell, and especially of Ayn Rand, since she described her philosophy of Objectivism as the natural outgrowth of Aristotle’s writings. All of them (excepting Aristotle) viewed the idea of God as unreasonable and unnecessary, and at that point in my life, reason became my god.

As the years went by, my “little bit” of philosophy developed into 20 years of study, and I assumed that old maxim could not apply to me. Still, I could not completely forget my nostalgic feelings for my Catholic upbringing. My lovely wife, Kathy, and I sent our children to Catholic schools. (I could rationalize that Thomas Jefferson, another of my idols, had sent his daughters to be taught by Jesuits in France.) Personally, I deeply wanted to believe, but I did not feel that in good conscience I could pretend to believe what I did not. I remember reading philosopher Mortimer Adler’s How to Think About God two times, years apart, hoping this would allow me to go there, but it did not quite bring me home.

Then, at age 43, along came a 13th century Dominican friar by the name of St. Thomas Aquinas, and he turned everything upside down — or maybe I should say, right side up!

When Charles Darwin first encountered the biological writings of Aristotle, he described modern scientific giants of his day as “mere schoolboys compared to old Aristotle.” So too, when I discovered the firsthand writings of St. Thomas Aquinas, I discovered that the modern philosophers I had been following were “mere schoolboys (and a schoolgirl)” compared to old St. Thomas Aquinas! St. Thomas showed me how faith and reason need not be in opposition, and that a person who thinks can also be a person who believes. What a liberation! Here was a true-to-life Superman of the Mind who loved God with all his heart and soul.

I found out not long afterwards that Pope Leo XIII, in his encyclical Aeterni Patris of 1879, had written about “those, who with minds alienated from the faith … claim reason as their sole mistress and guide.” Further, he noted that “apart from the supernatural help of God, nothing is better calculated to heal those minds and bring them into favor with the Catholic faith” than the writings of the Church Fathers and Scholastic philosophers — St. Thomas being their greatest exemplar. St. Thomas Aquinas was then the great hope for the conversion of modern intellectuals devoted to reason. Boy, did Pope Leo have my number, so many years before I was born!

St. Thomas allowed me to make the leap of faith without jumping away from reason. He, too, admired the Greeks, and he knew Aristotle exceedingly well. Some claim it is easier to grasp Aristotle’s philosophy by reading Aquinas than by reading Aristotle himself. St. Thomas did not merely throw Aristotle’s name around in passing, but he wrote complete commentaries on every single line of many of Aristotle’s books, and he peerlessly integrated logic and rational philosophy with Christian revelation in his masterful Summa Theologica. There is only one truth, wrote St. Thomas. Reason and Revelation are not contradictory. Faith does not contradict reason, but it takes us farther and higher than our reason can go, serving, as Pope Saint John Paul II would write in his encyclical Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason), as the two wings on which we rise to the truth.

St. Thomas’s writings were a real revelation to me. Little did I know that more than 700 years ago he had so soundly answered all the arguments of the atheists, who to this day proclaim that the idea of God is self-contradictory or completely unnecessary to explain the universe. His writings brought me back to Christ and His Church. The next thing I knew, we were back at Mass, and I began making up for a quarter of a century of lost time by devouring the New Testament and everything I could find by and about St. Thomas, St. Augustine, G.K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, and others. EWTN became my television fare, and The Journey Home my every Monday ritual. My family and I even wound up in Rome with a group from our parish during the week of Pope John Paul II’s funeral in April of 2005.

Admittedly, my story is a bit unusual in our time, although I have encountered a few folks since I’ve been back who were also drawn back by St. Thomas’s writings. Typically today, threats to Christianity come not so much from abstract philosophies as from distortions popularized in modern books and movies made for mass consumption. “Didn’t you know,” a co-worker asks, “that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married and had a child?” “It was Constantine, after all, who wrote the New Testament and came up with the idea that Jesus was God,” proclaims another. And a third informs me that the Church suppressed the Gnostic Gospels, like the Gospel of Thomas, which tells the “true story” with a much more pro-feminist message.

Interesting pronouncements, but I seem to recall from a little green book on my library shelf (An Exhortation to the Greeks), that Clement of Alexandria, who died before Constantine was born, was one of the many early Church Fathers who regularly spoke of Jesus as God. No marriage or children of Jesus are mentioned in any of the four Gospels. And wasn’t that Gospel of Thomas actually a bit negative in its stance on women, stating that women must become males to be worthy of the kingdom of heaven?

Personally, I was also wowed to see how God had used my 25 years in the atheistic wilderness to prepare me for my return to the Church and even to help me acquire skills that my formal training in psychology and avocation of philosophy help to do my own share to spread the wisdom of St. Thomas Aquinas with popular readers today.

Sometimes St. Thomas’ relevance came through in the most surprising of ways.

For example, one of my own specialty areas in psychology was memory. My master’s thesis examined memory improvement in adolescents through the use of particular memory strategies, and my doctoral dissertation examined the loss of memory and other higher intellectual capacities that accompanies dementia toward the end of life. You can imagine my amazement, upon my return to the Church, when I recalled that St. Thomas had been called “the patron saint” of memory-aiding techniques by a secular historian! (See Summa Theologica, II-II, Question 49, article 1 and his Commentary on Aristotle’s On Memory and Recollection for examples of the reason behind this.)

In turn, this discovery led to my current avocation of writing books about St. Thomas’s approach to memory, and then the virtues, the seven deadly sins, the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, and more (working now on a book about thinking like Aquinas). The Holy Spirit’s blessings have just kept pouring out to me and my family through the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas.

It seems to me that the most prevalent threat to Christianity today is not so much exposure to the bad philosophy of the godless philosophers as it is a lack of knowledge of the contents and history of one’s own faith — a knowledge that will not fall prey to popular distortions of Church history and a faith that can inoculate one from the bite of bad philosophy and heal those already bitten. I hope and pray that all Catholics will come to know and love Christ and His Church so well that they will never be led astray by bad philosophy or popular media. If such education is not supplied in their formal schooling, they can obtain it through study of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, through immersion in Catholic media like radio, television, and books, and for kindred souls, through the writings of St. Thomas and his popularizers.

As for me, St. Thomas Aquinas, the philosopher of God, saved me from the godless philosophers by applying the remedy of both faith and reason. I’ve felt wonderful and thankful to God ever since.