My father was raised a Roman Catholic but attended Houston Baptist University on a scholarship; my mother was raised in a Protestant household and baptized as a Protestant in her youth. She also attended Houston Baptist, where she met my father. Prior to the wedding, my mother “converted” to Catholicism, but her conversion was superficial at best. The priest who conducted her initiation classes swept her serious reservations about points of the Catholic Faith aside and hastened her toward Confirmation. She was confirmed, though she was never told to make a first Confession. Her weak adoption of Catholicism was short-lived and by the time I was born, both of my parents had abandoned Catholicism and had begun attending a Disciples of Christ church. This was where my mother’s family went to church and it bore a liturgical style similar enough to the Catholic Mass for my father not to feel too strong a discomfort in making the switch. The main thing I remember about this church concerned my desire to be baptized. Although I believed what was told to me about Jesus and knew that people who believed those things were supposed to be baptized, the church refused to allow me to be baptized because they thought I was not yet old enough to make a more serious act of faith.

Not long after, my parents switched to a Baptist mega-church in Houston. Despite my desire to be baptized at the Disciples of Christ church, I did not immediately respond to the altar calls at the Baptist church. I was eight when I did respond, spontaneously leaving the pew and my parents. I prayed the “sinner’s prayer” and was baptized. It was a long drive to this Baptist church, so my parents ended up joining a Baptist church closer to home. As I got a little older, I began to attend a youth group at an Evangelical Presbyterian church that some friends attended. I became very active, going on two mission trips to Mexico. When I was old enough, I also began attending the Baptist church’s youth services (switching sporadically between the two). Both groups were similarly structured. They had rock bands that played “praise and worship” music, in addition to sermons. The main distinction was that the Baptist church’s youth services were incredibly popular, being attended by a very large part of the “in” crowd from the local high schools. The band was very good, and the youth pastor was adept at putting on quite a show, including disco-balls, fog-machines, etc. Wednesday night services were often accompanied by altar calls and I remember seeing large crowds of people responding — sometimes more than once.

Theological depth

It seemed to me that the depth of faith being generated by these youth services was, at the very least, intellectually shallow.The Baptist church was particularly devoid of much concrete theological content except for preaching the necessity of faith and the general fittingness to be a good person in gratitude for salvation. The Presbyterian church provided more theological depth; it was in a debate with my youth pastor during a mission trip that I was first introduced to Calvinism, of which I became a zealous convert.

Later, the youth minister at the Baptist church decided his calling was to be an adult pastor and the youth group, which had been drawing crowds upwards of three to four hundred people during the week. I found this experience particularly informative and began to resent the forms of Protestantism that smacked to me of religious “entertainment.” I turned more completely to the intellectual side of Protestantism and began reading many theology books. I particularly enjoyed Wayne Grudem’s Systematic Theology, A.W. Pink’s The Sovereignty of God, and the works of Calvinist apologist Cornelius Van Til.

When I was old enough to drive, I stopped attending Sunday services at the Baptist church to which my parents still belonged and began attending a Presbyterian church (Presbyterian Church of America). As a high school graduation gift, I was given the complete works of Cornelius Van Til and John Calvin. I was so deeply immersed in Calvinism, that it came as no surprise that when choosing a college, I wanted something very religious and very Calvinist. My choice in 2001 was a well-known, conservative, and strongly Calvinistic college.

Sin

When one is convinced, as I was at this time, that one’s salvation is an assured thing as long as one “has faith,” then it is easy to rationalize one’s own particular sins as a necessary and uninteresting consequence of the human condition that should be generally avoided, but not with any urgency. It was not as though, I had thought, my salvation depended upon avoiding sin. It rested instead upon the genuineness of my faith and the sincerity with which I adhered to my Protestant faith. Though the false and dangerous part of this theology did not sink in while I was under my parents’ supervision, I became much more rebellious in college. I began to go to parties often. This seems like a benign part of college life to many, but this was a very bad and dangerous phase of my life that, as sin often does, made me very miserable and blinded me to the specific cause or nature of my suffering.

My grades suffered. Though I had an intellectual bent in high school, I was never really disciplined in my studying. Consequently, I was not a particularly good student at college. I chose philosophy as my major, because when I arrived I was told that the philosophy department was excellent. I had initially planned to study philosophy and theology, but in my first semester I took a theology class with the chair of the theology department, who was uninterested in taking seriously the tenets of the Reformation that I had gone there to study, and also did not seem particularly keen to defend much of anything that I took to comprise Christian orthodoxy.

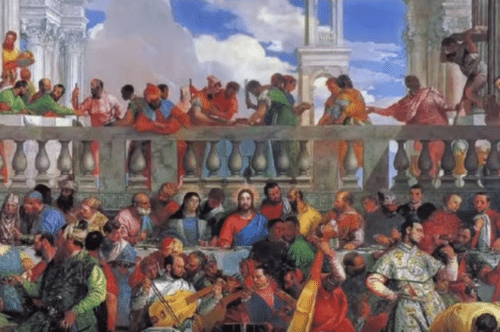

While in college, I began occasionally to attend an Associate Reformed Presbyterian church, toward which I had strong intellectual affinities. Here my Calvinism became even more virulent, adopting also the liturgical austerity of the early post-Reformation period. Thus, I was persuaded on the importance of not making or using any religious images, not singing any hymn not found in the Bible (i.e. using only the Psalms), and not accompanying these songs with any musical instruments. To do otherwise, I thought, was to offer a “strange fire” to God since He never commanded them, and therefore they were deeply wrong (see Leviticus 10:1-3). At a certain point, I had expressed interest to an elder in joining the Associate Reformed Presbyterian church, but nothing came of it.

My public acts of piety, such as going to church, soon after dwindled to almost non-existence. The friends with whom I had originally began attending the Presbyterian church became far more interested in “high church” liturgical styles and had stopped attending the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church. During my first year, I did not have a vehicle on campus, so I stopped attending church entirely, rather than attend where my friends wanted to go.

If I were to characterize the religiosity of this period of my life, it could be easily summarized as “bifurcated,” or going in different directions. Intellectually, I had a strong “faith” in the tenets of Protestantism, particularly as they were expressed in the Calvinist tradition. Yet Calvinism excused my sin as something God Himself did not see, since, so I believed, the righteousness of Christ had been imputed to me because of my genuine faith, covering over my sins so that He was blind to them, at least insofar as my salvation was concerned. My conscience naturally reproved the guilt of my actions, and yet I found in Reformation theology a rationalization of the guilt that prevented any serious and genuine reformation of my life. Protestants often hold this theological explanation of the unimportance of sin, so I think some degree of bifurcation is common. However, perhaps because I was more firmly convinced of the truth of this theological system than many other Protestants, I took God’s purported blindness to my sin seriously and became an increasingly worse person. The low point during this period was my being arrested for drunk driving as a sophomore. This event helped me take things quite a bit more seriously. In addition, in my junior year, I was quite fortunate to meet Amy, the woman that I would marry; she gave me far more stability.

An introduction to “a dying relic of European culture”

I graduated from college in 2005 and had been admitted into a philosophy Ph.D. program, which I began right after graduation. My wife, Amy, was a Catholic and I married her in the Catholic Church as a concession to her and her family. It didn’t matter much to me where we were married, though I thought of Catholicism with as much religious deference as I had toward lederhosen. To me, it did not seem to be a religion at all, but a dying relic of European culture.

Amy was raised as a cultural Catholic, which more firmly cemented this impression about Catholicism in my mind. Her mother was a convert to the Faith who, like my mother, was not given much by way of introduction and training. My wife’s father affectionately called himself a “C & E-er” (a Christmas and Easter Mass attendee only). During our first year of marriage, we both tried out each other’s church preference; neither of us liked the other’s church, so our resolution was to sleep in on Sundays.

A year or so passed, and we both felt discomfort in never going to church. During this time, Amy also wanted to discover more about her Faith, so we bought the book Catholicism for Dummies. She never really looked at it, but I was a reader, so I had most of the book read soon after we bought it. I came across something I had never really seen before: a distinction in sins, between those serious sins because of which one could be damned (i.e. “mortal” sins) and less serious sins (i.e. “venial” sins). I was floored to find that using artificial contraception and skipping Mass on Sunday without a serious reason were mortal sins. I showed Amy this after I read about it. She said she might have vague memories, if anything, of something called “mortal sin” — but she didn’t know what that meant or which sins were considered mortal.

After learning more about what the Catholic Church considers grounds for mortal sins and though I was definitely no Catholic, I did not want her to get into any sort of spiritual trouble, so we resolved to stop using contraception and start going to Mass on Sundays. We learned about Natural Family Planning and opted for that, which was a Godsend in more ways than one, since my wife had been having some health problems that completely went away after discontinuing hormonal contraceptives. I also began accompanying her to Mass, but I had serious reservations about the Catholic Faith — particularly about Marian doctrine — and so was resolved not to convert.

We began to talk a little about the Catholic Faith at this point, insofar as I would explain to Amy my objections to claims, such as the perpetual virginity of Mary or Mary’s sinlessness. Amy knew little about Catholicism and expressed a wish that I could find someone else to talk to about why Catholics believe what they do and who could better answer my objections. We did not find anyone. However, I had a book about the early Church that I had always intended to read, and thought that it might shed some light on why the Catholic Faith developed to hold the things that it did. I was again floored by what I read.

Challenging Reformation theology

In particular, as a Protestant, I had always had vague notions that the earliest Christians were essentially the same as Protestants today in theology and style of worship. The Re-“formation” was, I thought, all about re-“forming” Christianity so that it got back to the original Christianity bequeathed to us by Christ, removing from it all the superstitious and silly doctrines and practice imposed upon it in the Middle Ages by the Catholic Church. I soon found that these vague notions I held about the early Church could not have been more erroneous.

As I read these detailed summaries of the beliefs of the Fathers of the Church, I was startled in particular to find in them all the essential elements of contemporary Catholicism in embryonic form. Moreover, this mustard seed of the Catholic Church did not become visible a couple hundred years after Christ, but was present in the earliest recorded Christian writings, some predating or contemporaneous with what we have good reason to believe was the time that the books of the Bible were still being written! In brief, the earliest Church was the Catholic Church.

The area of doctrine that struck me most forcefully was the insistence of the early Fathers (particularly St. Ignatius and St. Polycarp, and even into the period of the apologists Tertullian and St. Irenaeus) on obedience in matters of faith and doctrine to the bishops and the centrality of Tradition (faithfully transmitted to us by the bishops) in the codification of Christian doctrine. Tertullian and Irenaeus were particularly forceful to me in showing that sola Scriptura (as it is understood and firmly believed by central figures in the Protestant Reformation) was a notion foreign to early Christians. Once I saw this in the Fathers, I was shocked to find strong support of it in Scripture.

I was even surprised to find early insistence by some Fathers upon Peter’s primacy as the Prince of the Apostles and the necessary submission to his successor as the chief steward of the authentic Faith. From this source, I thought, all other Catholic doctrines necessarily derive. For even if we saw no other Catholic doctrine present in the early period, save the necessity of believing the faith transmitted by the Pope, that would be sufficient. It is obvious that the popes have preached the Catholic Faith, and thus the Faith the early Christians would have today is authentically found only in the Roman Catholic Church. Of course, we find evidence for a broad range of uniquely Catholic beliefs and practices in the early Church, not just the doctrines involving Tradition and submission to the hierarchy, but my area of interest in philosophy was (and is) epistemology — that is, a study of what we know and how we know it — and seeing this point strongly pushed me toward Catholicism.

Prior to the actual decision to convert, I wanted to make sure I was not being hasty. I began reviewing many of my old theological sources to see if I had forgotten about central objections to Catholicism that I had not been particularly interested in during my youth. For instance, I read a lot of Calvin’s Institutes of Christian Religion, trying to find some argument against the Catholic Church he was leaving. I also reviewed the works of Van Til, whose apologetic method was supposed to prove the Calvinist form of Christianity distinctly. Both left me very unimpressed. I turned to two Protestant apologetics websites that I had found useful in my youth and, looking over their arguments against Catholicism, I found the websites’ arguments to be easily responded to in light of the research I had done into Catholicism.

Beyond the intellect

I was left without any mental objection to the Catholic Faith, but I was still a little wary. One of my old philosophy friends recommended I read Rome Sweet Home (or other books by Scott Hahn and similar convert authors) and, though not Catholic, he told me that praying the rosary was a powerful experience. As, perhaps, an intellectual exercise (at least at first), I did begin to pray the rosary — sometimes several times in a row, finding it deeply compelling. I also found myself more and more absorbed by the Mass. It was something strange and foreign to me, but there was also something to it that seemed solemnly important. I had been put off when attending Protestant churches sporting “high” liturgies while I was at college. Yet, there was something unique in the Mass that I could not describe, but that I believed I could sense. I am not a sentimentalist by any fashion, but I did feel a sort of magnetic attraction to the rosary and Mass.

It should be no surprise to say that I began RCIA soon after. I was confirmed in the Catholic Church in 2008. During this process, Amy also experienced a more authentic conversion to the Catholic Faith and was confirmed during the process (not having been confirmed as a youth).

The fruits of conversion

Several interesting things have happened since I converted. The first was that I found out from my Aunt Mary (my father’s sister) that she and her family had been praying for a long time that I would convert to Catholicism. (I knew nothing of this.) They had reasoned that the only way that my dad would return to the Faith of his youth would be through my conversion and the subsequent arguments that I would inevitably have with him about Catholic truths.

During my journey, these arguments did indeed occur. As I had been reading and being drawn to the Church, I had concurrently described my discoveries to my parents, who were politely “interested” in what I had to say, though disagreed with it. My father was more easily persuaded, recalling debates that he had with Baptists in college while he was still Catholic. My mother, however, was firmly opposed. A year or so went by, during which it was common (and increasingly so) for us to talk about Catholicism and the arguments for or against it. At a certain point, both my parents were intellectually convinced (my mother being particularly helped in this by the book Rome Sweet Home), but still wary of making a first Confession and actually returning to the Church.

An event helped change that. One afternoon, my mom and I were discussing Catholicism. At a certain point in the conversation, she interrupted me and said something along the lines of “Oh my goodness…” with a long pause, and then “Oh my gosh…” Of course, I asked her what was going on. She began to get choked up and told me that she had just remembered a dream she had the night before. She had dreamt that she was with my dad’s mom at a Catholic Mass. At the end of the Mass, my mom and my grandmother left and saw that the priest who had celebrated the Mass who was (as she described him repeatedly) “beautiful” and “glowing.” The memory of him was the reason she had been choked up and when she began actually describing him, she started to cry outright and quickly got off the phone with me. This was very out of character.

That happened on a Friday night and I thought about the dream all weekend. I didn’t think that an ordinary dream could have had such a powerful effect on my mom. On the following Sunday, I told my dad that I thought the dream wasn’t an ordinary dream and that the beautiful priest whom she saw glowing was not just some imagination, but a real Catholic saint who had interceded on her behalf and whom God had granted to show up in her dream. Thus, I told him that my expectation would be that at some point she would see a picture of the saint who was in her dream and recognize who it was. He asked me who I thought the priest might have been and I told him that the first one that sprang to mind was the English Cardinal John Henry Newman, a convert from Anglicanism. He hadn’t heard of him and afterward I talked to my mom for a few minutes and then got off the phone.

About ten minutes later, I got a frantic phone call from my mom. She had told me that “a very weird goose bump thing just happened.” The reason she was frantic was that, after getting off the phone with me, my dad had pulled up a picture of Blessed Cardinal Newman online. He didn’t say anything to her about it, but had simply pulled up the picture and asked her if she recognized the person. She instantly recognized him as the “saint” that was in her dream, but my dad refused to explain who he was and told her to call me to find out. I quickly explained to her who Cardinal Newman was and his significance; she was flabbergasted. Needless to say, she had never heard of Cardinal Newman, nor had she seen his picture. She talked to me for a few minutes more and got off the phone (she was, after all, still officially a Protestant at this point, though on the fence about converting).

Though I had been praying for their conversions, I hadn’t expected this. My mom held off telling my sister, Kristen, about the dream for a few days, because my sister had been pretty antagonistic toward my parents regarding Catholicism. When my mom finally worked up the nerve to tell Kristen about it, she was surprised at her reaction. Kristen had been talking to me about Catholicism too and on the same night that my mom had her dream, my sister had prayed to God to send her a sign that Catholicism was true and Protestantism was not. She explained to my mom that she had prayed God would specifically “send a dream,” because she thought she would be terrified if an angel came or something else very extraordinary happened. Kristen saw in this the exact sign she had prayed for and that day made the decision to convert to Catholicism, as did my mom and dad.

The last more immediate spiritual consequence of my conversion was the revitalization of the faith of my wife and her parents. My mother-in-law had always been a Mass-attending Catholic, but had never fully learned the totality of the Faith, particularly the necessity of going to Confession or the importance of avoiding certain sins. She remedied these defects very quickly. My father-in-law was a harder sell. He had grown up Catholic and had attended Catholic grade school; his attitude was that all those daily Masses and Stations of the Cross they had to do as kids more than made up for the missed Masses as an adult. It all evened out, he thought, and, after all, it seemed to him extreme to say that missing Sunday Mass without a good reason is any big deal. We prayed many rosaries for his conversion and it has now been several years since he returned to faithful Catholicism (going to Confession for the first time in 35 years).

My conversion has also deeply influenced my philosophy. My dissertation is a defense of a view in moral epistemology that is inspired, positively, by the works of Bl. Cardinal Newman and St. Thomas Aquinas, and negatively, by the desire to show why views of moral knowledge like those defended by heretical Catholic moral theologians since the 1960s (a view in contemporary philosophy often dubbed “moral intuitionism”) lead to moral skepticism.

That is a wonderful story of so many conversions. I pray constantly for my whole family’s conversion, especially for my daughter’s fiancé. My daughter is baptized Catholic and believes in God but she is not confirmed and does not attend Mass. She says she needs Sundays to see her friends. Please pray for the conversion of my whole family. Historically we are very anti-Catholic. I was baptized in John Knox’s Presbyterian Church of Scotland, went to a Low-Anglican primary school, Methodist and Baptist Sunday schools, High-Anglican grammar school, was a Methodist, Zenbuddhist, and finally member of the Mission Covenant Church before I became a Catholic.

Thank you Mr. Brian Besong for sharing your conversion story. I recommend this to my friends and family members to read.

I pray too for all those on their journey home to our Mother Church the Catholic Church.

Beautiful story!