One of my fondest memories growing up in the 1980s was the weekly Saturday afternoon creature double feature that used to play on our local UHF station in Detroit. Before the era of streaming and 4k Blu-rays, almost every major city in America had a channel that regularly showed movies like this. My favorite films during this time were the Godzilla films. The tone of these films began in a somber way, but as the series progressed, they catered more to children. Even with the shift in tone, the movies often contained humanistic themes and social commentary on Japanese culture in the 60’s and 70’s.

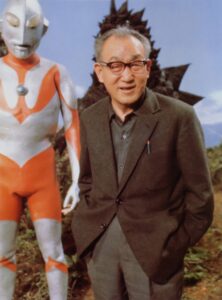

While there were many “fathers” of the Godzilla franchise, it was really one man’s imagination and creativity which gave Godzilla the look and personality that has made him the “mon-star” I grew to love — Eiji Tsuburaya, special effects master and convert to Catholicism.

Tsuburaya was born in 1901 to a Buddhist family in Japan. At a young age he showed great skill in art, seen as a remarkably skilled craftsman for his age. He was also fascinated with planes and considered becoming a pilot. At the age of 18 he found himself working at various movie studios learning the craft of both camera work and special-effects. During the years that followed, and especially during the Pacific War, he continued to hone his craft in special-effects, most notably in war time films that depicted air and sea battles. All of these experiences would serve him well when after the war he was hired by Toho Studios to create the special-effects for his most famous work: Gojira (1954). It was also during these early years, before Gojira, that he met his future wife, Masano Araki, whom he married in 1930.

Though Tsuburaya was often influenced by aircraft, special-effects, and set designs, it also seems that Masano had a profound impact on her husband’s faith, bringing him to Christ and His Church. (Masano herself was a convert, introduced to the faith by her sister.) Godzilla historian August Ragone notes that it was during these early years that their third son, Akira, was born, the first to be baptized as a Catholic. Masano began raising her sons as Catholics, and eventually led Eiji to convert as well. From all accounts, Tsuburaya was a faithful Catholic the rest of his life.

It was typical of Japanese culture to keep one’s religious faith rather private, but hints of Tsuburaya’s Catholicism can be gleaned from a number of his most iconic kaiju creations. Some have suggested that in his kaiju universe, Tsuburaya is more subtle like Tolkien than the more directly allegorical works of C.S. Lewis. I think it can be said that Tsuburaya’s love of fantasy and fairy tales for children found a perfect home in his adopted Catholic faith.

In a 1962 magazine article he talked about how his youth affected his later film making: “My heart and mind are as they were when I was a child…then I loved to play with toys and to read stories of magic. I still do. My wish is only to make life happier and more beautiful for those who will go and see my films of fantasy.”

This concern for providing places of joy for children was evident even during the war years. As Allied bombing raids were entering mainland Japan, Ragone recounts that “Eiji, Masano, and their children sought refuge in a bomb shelter, and, as the incendiaries fell, Tsuburaya told his children lovely fairy tales to calm them.” We see Eiji’s love for children in Godzilla’s transformation from humanity’s scourge to humanity’s savior and defender as the series progressed. Godzilla changed from a monster to be feared into to a savior who could be counted on and cheered.

Godzilla wasn’t the only monster providing clues of Tsuburaya’s growing faith. There was also the divine moth-like creature Mothra, the benevolent kaiju who often exhibits Christian ideals of self-sacrifice, compassion, and even resurrection. The clearest hint of his Catholicism, though, came in Tsuburaya’s own creation: Ultraman.

Godzilla wasn’t the only monster providing clues of Tsuburaya’s growing faith. There was also the divine moth-like creature Mothra, the benevolent kaiju who often exhibits Christian ideals of self-sacrifice, compassion, and even resurrection. The clearest hint of his Catholicism, though, came in Tsuburaya’s own creation: Ultraman.

In this TV series, an alien comes to earth and rescues a man from certain death by joining with him bodily. This union of space alien and man saves humanity from a series of monster-of-the-week foes. Who can forget how Ultraman would so often, with seconds remaining, make a cross with his arms and fire a spacium beam to defeat his (and humanity’s) enemies?

Ultraman, who united both the human and the otherworldly, overcomes every evil that is thrown at him through courage and self-sacrifice, a clearly Christian archetype.

Eiji Tsuburaya died on January 25, 1970. In addition to the private ceremonies of mourning and the funeral at their parish, a Catholic service was held in February on Stage No. 2 on the Toho Studios lot in his memory, extending the impact of his faith beyond the confines of his personal life, much like the messages of sacrifice and justice found throughout the works he poured himself into creating. Though dead for over 50 years, Tsuburaya’s legacy as the “Master of Japanese Monsters” continues today, with Ultraman and Godzilla still as popular and relevant as ever.

While the Saturday creature feature seems largely a relic of the past, I still love watching Godzilla DVDs with my youngest son. My little Goji buddy and I still enjoy being transported to Japan to watch our favorite monsters battle it out. There is always that wonderful knowledge that the man behind the monster was a fellow brother in Christ.