Long before cowboy churches entered the Protestant landscape of the United States, one quite well known cowboy made his journey into the Catholic Church. William Frederick Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill, was one the most famous figures of the American Old West. Gaining his moniker due to his work as a buffalo hunter after the American Civil War, Cody would go on to create Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a circus-type stage show portraying a version of life in the American West. This show would eventually become a world-wide phenomenon, traveling across the U.S. and Europe, and included Native Americans invited by Cody to tour with him to provide an accurate representation of their heritage.

William Cody was not an overly religious man for much of his life, though he grew up in a religious household, his mother a devout Quaker. Cody’s way of living certainly did not betray any affinity to a life of Christian virtue—rumors of his infidelity and drunkenness were widespread, especially after his attempt to divorce his wife. This began to change in the early 1900s, however, as his correspondence with his sister Julia would reveal. He writes,

“Let us show the Lord we are Christians. And will carry our cross. God ever bless you my patient brave sister. Remember our brave Christian mother and what she endured.” (Letters from Buffalo Bill)

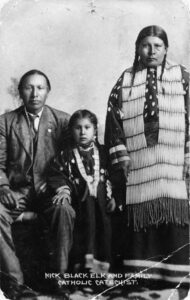

We do not know the full extent of what changed his heart, though there is much conjecture and folklore, the story changing with the storyteller. We do know that a number of the Native Americans who toured with Buffalo Bill were Catholic. One of those was Black Elk, an Lakota Sioux healer who himself was a convert to Catholicism, taking the name Nicholas at his baptism. While it does not appear that Nicholas Black Elk traveled with Buffalo Bill following his conversion, the timeline suggests that he quite likely may have been in attendance when Cody was granted an audience with Pope Leo XIII in March of 1890.

Given what we know, it is also a distinct possibility that the Native Americans touring with Buffalo Bill across Europe in later years, during Cody’s spiritual transformation, could have been recipients of Nicholas Black Elk’s instruction in the faith. Nicholas Black Elk became a trusted catechist to indigenous people across many tribes following his conversion, working alongside the Jesuit missionaries who were instrumental in his own journey into the Catholic Church.

As for Buffalo Bill, the fallout of a failed divorce, the witness of those on his tour and his commitment to their good, combined with the fruits of his audience with Pope Leo XIII worked together to help him turn his life around. He was “trying to live on earth as God would be pleased to have me live,” committed to remaining sober for the rest of his life and healing his relationship with his then estranged wife (Letters from Buffalo Bill). Eventually, William Cody would return to Colorado, living near his sister who had become a Catholic. With his life now committed to Christian living, Buffalo Bill would request to be baptized into the Catholic Church just before his death in 1917.

Like so many on the journey, Buffalo Bill’s life took a number of twists and turns on his way into the Church. He undoubtedly received inspiration and conviction from unlikely sources at the time, like the Native Americans he toured with and the difficulties in his marriage. Yet, we see that the persistence of God is undeniable—in his life and in ours.

*****

“For the last thirty years I have lived very differently from what the white man told about me. I am a believer. Accordingly, I say in my own Sioux Indian language, ‘Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name,’ as Christ taught us and instructed us to say. I say the Apostle’s Creed and I believe it all…I send my people on the straight road that Christ’s church has taught us about. While I live, I will never fall from faith in Christ.”

From The Last Testament of Nicholas Black Elk