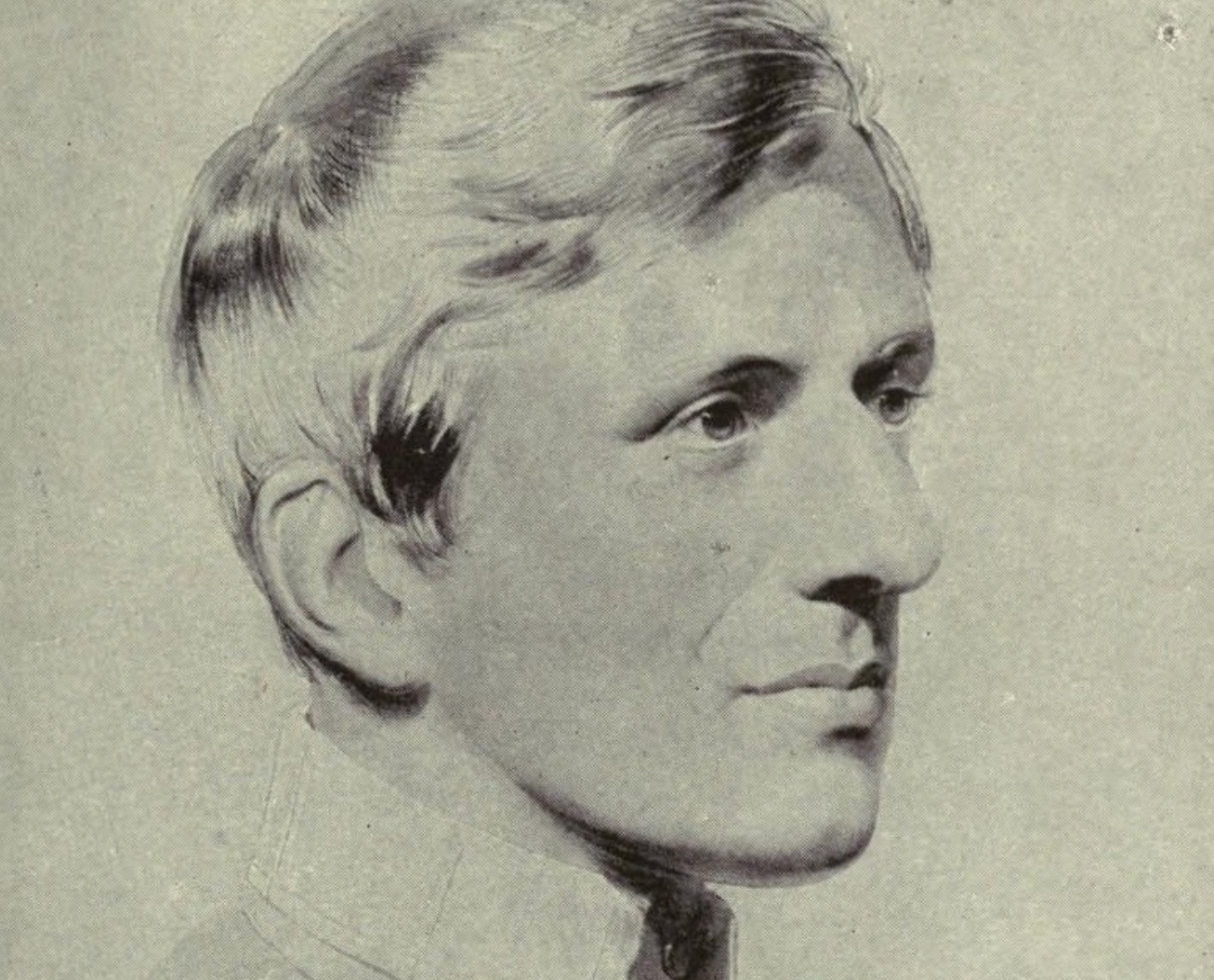

On Oct 13, 2019, Pope Francis celebrated the canonization Mass for St. John Henry Cardinal Newman, the brilliant 19th century theologian and convert from Anglicanism, whom many believe is destined to become a doctor of the Church.

Newman’s reception into the Catholic Church on Oct 9 (his feast day) in 1845, shook the foundations of the Anglican Church, and his journey to Rome the next year to prepare for Catholic ordination initially attracted considerable interest. But Newman had thought and prayed his way from Anglicanism to Catholicism in the relative solitude of his study, and his circle of Catholic friends was small. It was soon evident that in Rome he and his secretary Ambrose St. John would live in relative isolation. Newman for a time enjoyed a certain celebrity status but he doubted that anyone really understood him.

The Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, the center of the Holy See’s missionary endeavors, received them and gave them rooms at the Collegio Propaganda near the Spanish Steps. There, Newman and St. John would become ordinary seminarians. But who was going to educate the most perspicacious theologian of his time? It is perhaps comforting to hear his friend St. John report that the lectures were boring and somewhat lacking as pedagogical models, and so Newman would often fall to sleep in class. (Thankfully this does not appear to have been held against Newman in the cause for sainthood!)

Newman was left largely to himself, to continue his brilliant studies of the Church Fathers. Rome’s theologians had some doubts about his recently-published Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. Newman’s argument, that Catholic dogma was not, as it were, handed down from Mount Sinai but unfolded in a divinely-guided process of historical development in the life of the Church, was initially a very disconcerting idea for Catholic theologians hard-pressed to defend a tradition under siege from nearly every quarter. They naturally wondered about how sound this new convert really was.

So Newman, newly arrived from a different ecclesial world, was not well understood, and given his somewhat melancholic temperament, we are left with the distinct impression that his 1846-1847 academic year in Rome was certainly not about “making merry” over the return of a prodigal son of the Church (Lk 15:24). Newman, once the consummate insider of Anglican Oxford, is now an awkward and disoriented guest struggling to learn the customs of the house.

His first public act after his conversion, a funeral oration, was a humiliation, and the outcry even reached the papal ear. “We all need conversion,” Newman had said, so offending a congregation used to florid eulogies that someone suggested he should be thrown into the Tiber. Pope Pius IX offered Newman wise counsel about his awkward attempt to convert the English at that Roman funeral: “On such occasions honey is more suitable than vinegar.” But he was able to keep a self-deprecating sense of humor, as when he dutifully records his first meeting with Pius IX, who seemed “very cordial and friendly,” even though he had bumped his head against the Pope’s knee as he bent to kiss the papal foot (Letters and Diaries, XII,9).

His ordination retreat is extremely revealing. In his notes, I think that Newman has captured precisely what troubles the hearts of many former Protestant clergy who have approached the door of the Catholic Church — the surrender of personal autonomy, the loss of status, the difficulty and uncertainty of beginning again. Here are some representative excerpts:

His ordination retreat is extremely revealing. In his notes, I think that Newman has captured precisely what troubles the hearts of many former Protestant clergy who have approached the door of the Catholic Church — the surrender of personal autonomy, the loss of status, the difficulty and uncertainty of beginning again. Here are some representative excerpts:

• “So far as I know I do not desire anything of this world; I do not desire riches, power, or fame; but on the other hand, I do not like poverty, troubles, restrictions, inconveniences … I like tranquility, security, a life among friends, and among books, untroubled by business cares … In almost everything I like my own way of acting.”

• Newman would often feel embarrassed and self-conscious, “like a person acting in a new and unfamiliar role.” He had grown accustomed to a very public life as a mover and shaker in the Anglican Church. Now he seems to crawl along the ground when he wants to fly. He laments the loss of friends. “I feel acutely aware that I am no longer young, but that my best years are spent, and I am sad at the thought of the years gone by; and I see myself to be fit for nothing, a useless log.”

• Newman is acutely aware that he has lost the “natural and in- born faith” he had as a young man. “Now I am much afraid of the priesthood, lest I should behave without due reverence in something so sacred.” His faith in the efficacy of prayer and his confidence in the Word of God seem to have departed from him at precisely the time he needed them most. “The increasing years have deprived me of that vigour and vitality of mind which I once had and now have no more … My mind wanders unceasingly; and my head aches if I endeavor to concentrate upon a single subject.” (Tristram, Henry, ed. Autobiographical Writings, p. 245-248.)

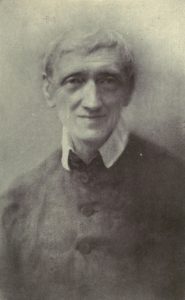

It was the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola that brought him precisely to the point he needed to be. As he knelt before the Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, in St. John Lateran on May 29, 1847, to receive ordination in the Catholic Church, some 43 very productive years lay ahead of him. But first, in order to receive this indelible mark from Christ and the Catholic Church, “those who belong to Christ Jesus have put to death their human nature with all its passions and desires” (Gal 5:24).

Those who have made similar journeys to the Catholic ministry are well aware that this is not a simple transition. There are many points of convergence between the separated churches and the Catholic Church, but there remain substantial differences as well. Perhaps there is no better a reminder of the profound difficulties of reconciling divided Christian communities than the experience of those who cross these frontiers as individuals. And so Newman’s canonization was a time of rejoicing for those who care deeply about Catholic unity. St. John Henry Newman is an intercessor “who has been tempted in every way that we have,” but who nevertheless pressed forward with great faith toward the new life of full communion. Every one of us has been profoundly affected by the witness of this man, and we truly owe him an enormous debt of gratitude.

Newman’s contribution to the Catholic Church is simply overwhelming. The beneficial changes he helped bring to the discipline of Catholic theology transformed the Church’s outlook and gave her a confidence to engage the world that resulted in some of the most significant accomplishments of the Second Vatican Council. Some have called Newman one of the most influential fathers of Vatican II, and in this we are reminded of St. Hilary of Poitiers sixteen centuries earlier, the exile who brought back the best part of the Eastern Christian tradition to enrich the Catholic Faith in the West.

There are many who share Newman’s own experience of finding the Catholic Church by searching deep within their own tradition. “The more you tried to be good Anglicans, the more you found yourselves drawn in heart and spirit to the Catholic Church” (Certain Difficulties Felt by Anglicans, p. 292). This is that wonderful principle at work, where those elements of sanctification and truth found within other ecclesial communities lead inexorably toward Catholic unity

(Lumen Gentium 8). We all have a part to play in this unfolding vocation of the Catholic Church, however modest it may seem to us, to draw all of the good things of God’s creation into perfect communion with Christ the Head. By stirring

up and contributing those gifts of faith and service that the Holy Spirit has already infused in us, we contribute our part to the catholicity of the whole Church. This character of universality is the goal to which the Catholic Church strives con- stantly (Lumen Gentium 13).There are many who share Newman’s own experience of finding the Catholic Church by searching deep within their own tradition. Share on X

To speak of Newman’s enduring ecumenical significance may seem strange when considering a man who changed his allegiance so dramatically and who described his old relationships as “the parting of friends.” But we have the gracious assessment of Edward Pusey, who had once been Newman’s most important colleague for the Catholic Revival in Anglicanism but could not in the end follow him. He called his friend’s conversion “perhaps the greatest event which has happened since the Communion of Churches has been interrupted.” And the reason why? “If anything could open their eyes to what is good in us, or soften in us any wrong prejudices against them, it would be the presence of such an one, nurtured and grown to such ripeness in our Church, and now removed to theirs” (Liddon, H.P., The Life of Edward Bouverie Pusey, II, 461).

Newman himself was unwilling to accept that this should be the end of the story. Cardinal Avery Dulles summed up Newman’s position so clearly: “Those who receive the grace to recognize the unique claims of the Catholic Church have a duty to act. If they do not act upon the knowledge granted to them, they are in serious danger of losing their souls” (Newman, p. 121; see Lumen Gentium 14). Many now argue that the ecumenical movement has set aside this manner of speaking, that the way of personal conversion must be handled with great discretion, to be described as simply the private exercise of conscience. Obviously I must demur on this point, firmly believing that genuine ecumenical progress requires prophetic actions that are resolutely ordered toward the Church Our Lord founded on St. Peter.

Thank you, St. John Henry Newman, for following so faithfully that kindly light which brought you home. Pray for us!