My friend, Sean, watched his father, Henry, die. Henry had been a WWII hero, a flying Tiger. Henry radiated Yankee independence, frugality, and self-sufficiency. He built his own house in Connecticut. He loved time in the woods. He raised his children well. But now he was gone.

Sean’s mother, Mary, continued to live in their family home for the next few years, until she chose to move to Florida. My friend, Sean, helped her clean out the decades of belongings and collections from the family home so she could sell it and relocate. Fifty years of memories had accumulated in that old house.

On the last day of moving out of the old house, Sean took one last walk-through, just to reminisce on years gone by and also to look for any possessions that had been missed in the packing. In his parents’ bedroom, Sean noticed an odd screw in the ceiling, an object that had never before captured his attention. Sean knew his dad and knew that the screw surely had some purpose, so he stepped on a stool to look at the screw in the ceiling. When he removed the screw, a panel slipped out of the ceiling. Behind the panel rested two Folger’s Coffee cans, each of which was filled with cash. The thought occurred to Sean that, if his father had hidden cash in one place, there might be others, so Sean soon discovered screws, panels, and coffee cans in holes in the wall all around that old house. By the end of the hunt, Sean had found more than $5,000, hidden years before in the old house by a Depression-era man who knew what we all now know: you cannot always trust banks. Instead of using banks, Henry had carefully hidden his treasure in the ceilings and walls of his old house.

For the first thirty-plus years of my life, the Catholic Church was just an old house. To someone who had grown up Methodist, the descendant from at least five generations of Methodist pastors in the South, the Catholic Church existed in my world simply as an old house. The Catholic Church was old and historic, often architecturally remarkable, but never something that attracted my attention in any real way.

Even in my nearly twenty years as a Methodist pastor, I neither liked nor disliked the old house of the Catholic Church. It meant nothing to me; I had no reason ever to notice its existence. It was just an old house, with some old rituals, old buildings, and old ideas. Along the way, however, God began to reveal to me the treasures hidden in the life of the old house known as the Catholic Church. Over time, as I discovered those hidden treasures, they proved so powerful and meaningful that they led me home to the Catholic Church.

Six hidden treasures, in particular, I discovered in the Catholic Church, but three stand out most of all. And I found them in various parts of the house.

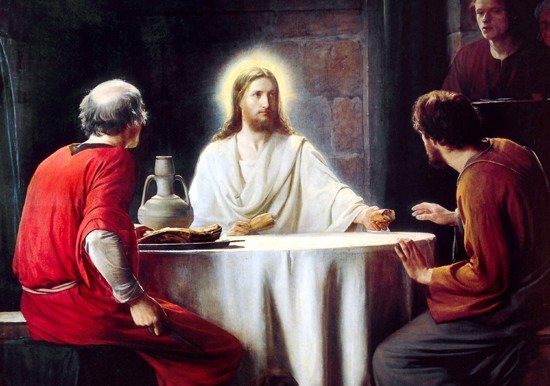

The Dining Room: The Treasure of the Eucharist

I found a hidden treasure in the dining room of the old house, but it took fifteen years for me to realize it. This discovery began my journey home and also proved to be the climax of that journey.

After I completed seminary at Emory University in Atlanta, my family and I moved to New Haven, Connecticut, to enable me to pursue a Ph.D. in New Testament and Early Christian Origins. Of the four students admitted to the degree program that year, one was a Presbyterian, one a Jesuit, one a Dominican, and, of course, I was a Methodist. The Dominican friar, Father Steven, and I immediately became close friends in our first week at Yale, and he opened the doors to the Catholic Church for me for the first time.

In our second year at Yale, Father Steven arranged for the two of us to give Lenten lectures to a group of cloistered Dominican nuns in North Guilford, Connecticut. In their monastery, God planted the seeds for my conversion, seeds which took nearly sixteen years to come to fruition, and seeds which I did not even realize were being planted at the time.

Father Steven and I enjoyed a wonderful time with the nuns at the Monastery of Our Lady of Grace. I discovered later that I had been the first male who was not an ordained Catholic priest ever to instruct the sisters behind their enclosure. It was a rare privilege and blessing. Our lectures focused on Thomas Aquinas, John Wesley, sanctification, and the places where our beliefs intersected far more than we had anticipated. We enjoyed great interaction and conversation with the nuns. After our last lecture, we reserved time for questions and answers. For many of the sisters, I was the first Methodist pastor they had ever met.

One sister, whom I call “Sister Rose,” raised her hand and said something like, “Allen, thank you for having come these past few weeks. We’ve enjoyed your teaching. You sound so Catholic. After hearing you, I can’t help but wonder, why aren’t you a part of the Church?” The question startled me. “I AM a part of the Church,” I responded. It had never occurred to me to use that kind of language: a part of THE CHURCH.

It took me a moment to realize what she was saying. Then I responded that there were a handful of reasons why I was Methodist as opposed to being Catholic. I mentioned one reason was the Eucharist. I told her, “It just seems obvious to me that, when Jesus said that He was the Bread, He was speaking metaphorically. I mean, it is bread and juice. I really do not understand why you all take it so literally. It is a symbol.”

Sister Rose then came right back at me, kindly but directly. “Well, you are a New Testament scholar, right? So why does Jesus say …” She then began to walk me through John 6 and Jesus’ teaching on the Bread of Life. She then moved to 1 Corinthians 11 and pointed out where Paul uses the language of Jesus, “This is my body … this is my blood.” She schooled me for about five minutes! Then she concluded, “What don’t you understand, Allen?” We all laughed, I shrugged it off, and we moved on.

Looking back, however, God planted a seed at that moment. That seed, in the end, led to my conversion.

In the years that followed, God continued to water that seed, often in unseen ways. For example, when my family and I would vacation, I usually worshipped at a Catholic church, which may seem unusual for a Methodist pastor. As a Protestant pastor, I normally had about four Sundays off per year. I always wanted to worship somewhere since those Sundays were precious occasions when I did not have the responsibility of leading worship. However, worshipping in towns where I knew no Protestant pastors meant that I would be “rolling the dice” since most Protestant worship experiences usually revolve around the pastor’s sermon rather than the eucharist. I did not want to squander the handful of Sundays where I could worship on my own by attending a church where I had no idea what the quality of the sermon would be. So I usually worshipped at a Catholic church where I knew exactly what I would get — not so much a sermon, but a timeless liturgy centered on the Eucharist, the Creed, and the sacrifice of our Lord. Frankly, I never thought much about it other than when our family was on vacation.

As time passed, however, I grew increasingly uncomfortable with my role as pastor and the emphasis on the sermon as the centerpiece of worship. As the pastor of the largest Methodist church in the Southeast at that time (in terms of average worship attendance on a normal Sunday), I found that discomfort put me in an increasingly awkward position. Only then did I begin to examine why the Catholic Church felt like home when I was on vacation. It was because of the altar as centerpiece and the Eucharist as focal point.

Again, this transformation occurred over time, not in some midday epiphany. God put pieces of the jigsaw puzzle together in my spirit one at a time over many days and years. But as I reflected on the early Church Fathers and how they saw the Real Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist, and on the early martyrs who went to their deaths accused by earthly authorities of being cannibals for their consumption of the Body and Blood, God changed my heart.

Such a change of heart was only confirmed by the art of Salvador Dali and then in my reading of Flannery O’Connor and Thomas Aquinas. O’Connor, in her famous comment in a letter to a friend, says regarding a Protestant’s dismissal of the Eucharist as merely a symbol, “Well, if it is just a symbol, all I can say is to hell with it…. It is the center of existence for me; all the rest of life is expendable.” And Aquinas, while celebrating Mass himself at the altar, had such a moving experience of the Real Presence of Christ that he reflected, “All that I have written seems to me like straw compared to what has now been revealed to me.”

Ultimately, I realized I had nothing to “protest.” Why was I a “Protestant”? I had no real reason to dissent from Mother Church, and when you have no reason, you go home. So I did. I came home because I had discovered the treasure of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, served in the dining room of this old house all over the world every day at the Mass.

The Kitchen: The Treasure of Holiness

During our three years in New Haven, my family and I encountered suffering and struggle unlike anything we had ever experienced before or since. I battled ulcerative colitis, a battle that culminated two years after its onset with the removal of my entire colon. My wife suffered two painful miscarriages. We already had two daughters and were delighted to receive more, but that plan failed to materialize. Shortly after the removal of my colon, I was diagnosed with melanoma. Fortunately, the diagnosis came early enough that the cancer was not life-threatening. Nevertheless, for our little family of four, these three years proved to be a crucible of suffering and purification that we had not anticipated, being a thousand miles away from home, with no family anywhere in the vicinity.

To make matters worse, for the first time in my life, I was at the bottom of my class. Of the four of us in the Ph.D. program, I clearly was the weakest when it came to academic preparation. My weakness revealed itself most plainly in our coursework in classical Greek. Each day that class presented the greatest struggles I have ever faced in a classroom.

Fortunately, my good friend, Father Steven, was far better prepared than I was. So I usually stopped by the priory where he lived each day on my walk home from classes. He could offer wisdom and guidance to help me. I entered the priory from the rear door, which led into the kitchen. I would sit and chat with the cook, Mary, until Father Steven came downstairs to work with me for a few minutes at the kitchen table.

Nearly every time I entered the kitchen, I met Father Cajetan Sheehan, O.P. Father Caj was eighty-nine when I met him. He stood about 5’2” and weighed perhaps 120 lbs. A wisp of a man. With a fiery spirit. And an aura.

Father Caj had “retired” from more than a half-century of pastoring, and retirement had evolved into a new ministry of prayer. Each morning and each evening, he and the other priests gathered for prayer. Some attended as they could; Father Caj was always there. Prayer permeated Father Caj’s life.

Without fail, each time that I saw him, Father Caj asked about my health. He asked about my wife, and he asked about my children. Every time. Without fail. And each time, without fail, he would say in his curmudgeonly New-England-Catholic-priest kind of way, “Well, I’ve been praying for all of you.” I knew those were not empty words. Prayer permeated Father Caj’s life.

When he retired, the secretary at his new home, St. Mary’s Priory, always knew that if someone in the parish needed a pastor in an emergency, Father Caj was the one to call. He stood always ready and always eager to go. At age eighty-nine, Father Caj stood ready to do the right things rather than merely the easy things.

When I met him, Father Caj still wore the same clothes he had been wearing for nearly thirty years. He took his small pension each month and placed it in its entirety in the Poor Box, the small box at the front of the church where believers could give to help ease pain and hurts of others. The parish where he lived provided all that he actually needed, and Father Caj figured that was enough. So he gave all that he had. At eighty-nine.

I will always remember the day that I stopped by the kitchen and ran into Father Caj. I knew that he had been in continuous prayer for a friend of ours. When I saw him, his head was swollen with a large bruise on it. “Father Caj, what happened?” I asked. His matter-of-fact reply came, “Oh, I was in the prayer chapel, and I was praying for you. And I fell asleep and hit my head on the railing.” He bowed up with just a touch of pride, the first time I had ever seen someone with a red badge of prayer courage.

I experienced, in a way I had never experienced before, that Father Caj had a deep aura of holiness that comes only with time. Father Caj possessed a holiness, probably without ever realizing it, that most of us will never attain. A life of faithful prayer, generous and sacrificial giving. A life of eager, willing, and joyful service. Caj and Jesus were good friends. The Spirit of God flowed so deeply in Caj’s veins that it nearly oozed out of his pores. Caj was walking closely with Jesus — seeking to do that which would be helpful and to avoid that which would be harmful.

That holiness never landed him on any magazine cover; it never made him wealthy beyond compare. It just made him a whole lot like Jesus.

And that holiness made an impression on me. An impression that never left me.

Why had I never encountered anyone this holy before? The question just turned over in the back of my mind for years, slowly cooking in my spiritual crockpot.

Then, I encountered Pope John Paul II, a man from whom holiness emanated, even through a television. His holiness attracted me like a magnet.

As a Methodist, I knew the theology of John Wesley and his emphasis on holiness. I believed that theology, and I yearned for holiness in my own life. But I had never encountered holiness like that which I observed personally in Father Caj Sheehan in the kitchen of St. Mary’s Priory or vicariously in Pope John Paul II through my reading and viewing.

God put these odd jigsaw pieces together for me through the writing of Thomas Merton. While serving as a Methodist pastor, I normally took my monthly daylong retreats at the Cistercian monastery on the east side of Atlanta. The silence and solitude moved deeply within me. Oddly, I had never considered why I chose a Catholic monastery for my monthly retreats, although it seems a bit obvious now, huh?

One afternoon, I was reading Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain, while sitting in the library at the monastery. The words leapt off the page.

First came the words that captured what I had been considering for years but had never been able to articulate. “Professor Hering was a kind and pleasant man with a red beard, and one of the few Protestants I have ever met who struck one as being at all holy; that is, he possessed a certain profound interior peace …”

Merton was right. Holiness comes with a profound interior peace, and in the busyness of Protestantism, much of which produces Kingdom fruit, I had rarely encountered anything like the holiness I had encountered in several Catholics. In fact, in the monasteries and other settings, I had even encountered whole pockets of holiness. In Father Caj, Pope John Paul II, not to mention the witness of the Dominican sisters, Brother Lawrence, and countless others, there resided a holiness that I yearned to experience for myself in some measure. A holiness rarely found in my experiences as a Protestant. A holiness that flows from God through the Eucharist in His Church to us.

That holiness is God’s calling and promise for each believer, even me. It is a sure thing in 1 Thessalonians 5:23–24 where the Apostle Paul writes, “May the God of peace himself sanctify you wholly; and may your spirit and soul and body be kept sound and blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. He who calls you is faithful, and he will do it.”

I experienced that deep level of holiness in the kitchen of this old house. And in many ways, that treasure called me home.

The Storage Shed: The Treasure of God’s Family

My grandmother died in Ohio in 1991. She had lived in the same house for nearly sixty years, a small, four-room house near the Ohio River.

When she died, my brother’s family and my own joined my parents in Ohio for the funeral and to settle the simple estate. My mom, who is an only child, coordinated the affairs and asked my brother and me to clean out the storage shed in the back yard.

In the shed, we found a large footlocker, looking eerily like a treasure chest. It was locked but not heavy. No one had the key, nor did anyone know the key’s whereabouts, so my mind instantly began to flash with the idea of a hidden pirate’s treasure that my grandmother had stored for years and never revealed to anyone. A treasure of jewels and gold only to be discovered after her death, a treasure that was going to make me rich beyond my wildest imagination and dreams!

My brother and I pried open the treasure chest with a screwdriver, eagerly anticipating the riches that would soon be ours. As we opened the footlocker, we discovered it was filled to the brim with … old pictures. Old, black-and-white photos. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of them. All kinds of people in all kinds of poses. These photos clearly captured my grandmother’s family members, whom I had never met, and friends who had filled her life with joy.

We sifted the pictures through our fingers, and then turned them over, only to discover that none of them contained any writing or identification whatsoever. Sadly, we realized we were in possession of countless photos of people who were important to us, but we had no idea who the people were. It was almost like being an orphan. You know you have relatives; you just are not sure who they are.

As a Protestant, I had always known “of” the saints. I just really did not know who they were. I was like a spiritual orphan who had photos of thousands of relatives in the family of God, but had no names or identification for the photos.

In fact, on one journey to England to attend the World Methodist Conference, I visited holy sites like St. Paul’s Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, and Canterbury. The event frustrated me to no end because I realized how little all we Methodists had in common other than the name “Methodist” and a loose claim to the paternity of John Wesley. However, while attending the conference and traveling England, I encountered St. Thomas More and St. John Fisher, old relatives whom I had not encountered before. When I heard their stories, and gazed at their “photos”, I saw men of great courage. Men who had lost their lives (by losing their heads) for standing for truth against King Henry VIII.

Again, it is my own fault. As I had never really considered teachings on the Eucharist, I just never had really given much thought to where the Methodist Church had come from and its origins in the Church of England. The Methodist Church had always been an assumption for me. My family had been saturated in Methodism for as many generations as we could trace. My relatives had launched Methodist colleges, edited Methodist newspapers, unified Methodist denominations, and led Methodist congregations. I myself had been a pastor and leader in the Evangelical realm of the United Methodist Church. Still, I had never seriously considered the origin and authority of my own spiritual home.

St. John Fisher emerged as the chief supporter and trusted counselor of Queen Catherine when Henry sought his divorce. He declared himself ready to die on behalf of the Church and her teaching on the sanctity of marriage. Fisher spent time in prison, lost all his property and possessions, suffered countless indignities and humiliations, and ultimately lost his life for his stance.

In May 1535, Pope Paul III, made Fisher cardinal priest of St. Vitalis. King Henry replied to the pope, telling him not to send the cardinal’s hat to England, saying that he would send Fisher’s head to Rome instead. Fisher was beheaded on Tower Hill, and his head was stuck on a pole on London Bridge for all to see. Fisher became one of the fifty-four English martyrs of the Church during the Reformation.

Fisher had much to protest. He stood between truth and error, defending truth at any cost. Somehow, I had never absorbed that story before, and it sank deeply into my spirit. I had a bold relative in the faith who called into question the lineage and authority of my own tradition. The questions became clear in my mind: Did I stand in the way of King Henry or in the way of St. John Fisher and the Church? What am I protesting? I could find no justifiable reason to be separated from the Church. Again, I discovered that God was calling me home.

Becoming Catholic has filled my life with the names and faces of countless saints and relatives in the faith. The New Testament uses “family” as a description of the Church more than any other term. I now have a very large family. Family members who walk alongside me, cheer me on, pray with me, encourage and inspire me. Family members from whom I had been distanced in my Protestant formation. Family members who once lay unidentified in the storage shed of the old house but now make themselves known in marvelous ways. Family members who welcome me with gladness into the greatest family of all!

“Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight, and sin which clings so closely, and let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us” (Heb 12:1).

In the Atlanta airport, a three-story escalator leads you from the underground tram system up to the baggage claim area. At the top of that steep escalator is a waiting area where moms and dads, sons and daughters, friends and family, stand eagerly awaiting the arrival of their beloved family member who is arriving from a faraway land. The waiters stand with signs, with balloons, and with eager faces teeming with anticipation. They stand waiting and peering at the top of the escalator as each passenger pops into view. “Will the next one be our family member?” “I hope so.” “Is that him?” “Isn’t she supposed to be here by now?” The waiting area literally tingles with anticipation. Each passenger arrives to squeals of joy, roars of laughter, tears, embraces, and twirling around in the arms of the family.

That is how I envision heaven. Each of us arrives one by one into the presence of God, appearing on the horizon like travelers from a faraway land. Our family members and “heavenly greeting team” stand waiting, tingling with delight and joy as they anticipate our arrival.

I do not think that I get to pick, but I can hope that my greeting team includes not only my father and grandmother, but also John Fisher and John Paul II, Teresa of Avila and Catherine of Siena, Father Caj, Sister Rose, Mary, and Jesus Himself. All waiting to receive me as the newest arrival into the family of God once and for all. Waiting to show me around the newest renovations of this old house. Waiting to say, “Welcome home!”