I was born into a loving, believing community, a Protestant “mother church” (the Reformed Church) which, though it had not for me the fullness of the faith, had strong and genuine piety. I believed, mainly because of the good example of my parents and my church. The faith of my parents, Sunday school teachers, ministers, and relatives made a real difference to their lives, a difference big enough to compensate for many shortcomings. “Love covers a multitude of sins.”

I was taught what C. S. Lewis calls “mere Christianity,” essentially the Bible. But no one reads the Bible as an extraterrestrial or an angel; our church community provides the colored glasses through which we read, and the framework, or horizon, or limits within which we understand. My “glasses” were of Dutch Reformed Calvinist construction, and my limiting framework stopped very far short of anything “Catholic!” The Catholic Church was regarded with utmost suspicion. In the world of the forties and fifties, in which I grew up, that suspicion may have been equally reciprocated by most Catholics. Each group believed that most of the other groups were probably on the road to hell. Christian ecumenism and understanding has made astonishing strides since then.

Dutch Calvinists, like most conservative Protestants, sincerely believed that Catholicism was not only heresy but idolatry; that Catholics worshipped the Church, the pope, Mary, saints, images, and who knows what else; that the Church had added some inane “traditions of men” to the Word of God, traditions and doctrines that obviously contradicted it (how could they not see this? I wondered); and, most important of all, that Catholics believed “another gospel,” another religion, that they didn’t even know how to get to heaven: they tried to pile up brownie points with God with their good works, trying to work their way in instead of trusting in Jesus as their Savior. They never read the Bible, obviously.

I was never taught to hate Catholics, but to pity them and to fear their errors. I learned a serious concern for truth that to this day I find sadly missing in many Catholic circles. The typical Calvinist anti-Catholic attitude I knew was not so much prejudice, judgment with no concern for evidence, but judgment based on apparent and false evidence: sincere mistakes rather than dishonest rationalizations.

Though I thought it pagan rather than Christian, the richness and mystery of Catholicism fascinated me — the dimensions which avant-garde liturgists have been dismantling since the Silly Sixties. (When God saw that the Church in America lacked persecutions, He sent them liturgists.)

The first independent idea about religion I ever remember thinking was a question I asked my father, an elder in the church, a good and wise and holy man. I was amazed that he couldn’t answer it. “Why do we Calvinists have the whole truth and no one else? We’re so few. How could God leave the rest of the world in error? Especially the rest of the Christian churches?” Since no good answer seemed forthcoming, I then came to the explosive conclusion that the truth about God was more mysterious — more wonderfully and uncomfortably mysterious — than anything any of us could ever fully comprehend. (Calvinists would not deny that, but they do not usually teach it either. They are strong on God’s “sovereignty,” but weak on the richness of God’s mystery.) That conviction, that the truth is always infinitely more than anyone can have, has not diminished. Not even all the infallible creeds are a container for all that is God.

I also realized at a very young age, obscurely but strongly, that the truth about God had to be far simpler than I had been taught, as well as far more complex and mysterious. I remember surprising my father with this realization (which was certainly because of God’s grace rather than my intelligence, for I was only about eight, I think): “Dad, everything we learn in church and everything in the Bible comes down to just one thing, doesn’t it? There’s only one thing we have to worry about, isn’t there?”

“Why, no, I don’t see that. There are many things. What do you mean?”

“I mean that all God wants us to do — all the time — is to ask Him what He wants us to do, and then do it. That covers everything, doesn’t it? Instead of asking ourselves, ask God!”

Surprised, my father replied, “You know, you’re right!”

After I’d had eight years of public elementary school, my parents offered me a choice between two high schools: public or Christian (Calvinist), and I chose the latter, even though it meant leaving old friends. Eastern Christian High School was run by a sister denomination, the Christian Reformed Church. Asking myself now why I made that choice, I cannot say. Providence often works in obscurity. I was not a remarkably religious kid and loved the New York Giants baseball team with considerable more passion and less guilt than I loved God.

I won an essay contest in high school with a meditation on Dostoyevski’s story “The Grand Inquisitor,” interpreted as an anti-Catholic, anti-authoritarian cautionary tale. The Church, like Communism, seemed a great, dark, totalitarian threat.

I then went to Calvin College, the Christian Reformed college which has such a great influence for its small size and provincial locale (Grand Rapids, Michigan) because it takes both its faith and its scholarship very seriously. I registered as a pre-seminary student because, though I did not think I was personally “called” by God to be a clergyman, I thought I might “give it a try.” I was deeply impressed by the caption under a picture of Christ on the cross: “This is what I did for thee. What will you do for Me?”

But in college I quickly fell in love with English, and then Philosophy, and thus twice changed my major. Both subjects were widening my appreciation of the history of Western civilization and therefore of things Catholic. The first serious doubt about my anti-Catholic beliefs was planted in my mind by my roommate, who was becoming an Anglican: “Why don’t Protestants pray to saints? There’s nothing wrong in you asking me to pray for you, is there? Why not ask the dead, then, if we believe they’re alive with God in heaven, part of the ‘great cloud of witnesses’ [Heb 12] that surrounds us?” It was the first serious question I had absolutely no answer to, and that bothered me. I attended Anglican liturgy with my roommate and was enthralled by the same things that captivated Tom Howard and many others: not just the aesthetic beauty but the fullness, the solidity, the moreness of it all.

I remember a church service I went to while at Calvin, in the Wealthy Street Baptist Temple (Fundamentalist). I had never heard such faith and conviction, such joy in the music, such love of Jesus. I needed to focus my aroused love of God on an object. But God is invisible, and we are not angels. There was no religious object in the church. It was a bare, Protestant church; images were “idols.” I suddenly understood why Protestants were so subjectivistic: their love of God had no visible object to focus it. The living water welling up from within had no material riverbed, no shores, to direct its flow to the far divine sea. It rushed back upon itself and became a pool of froth.

Then I caught sight of a Catholic spy in the Protestant camp: a gold cross atop the pole of the church flag. Adoring Christ required using that symbol. The alternative was the froth. My gratitude to the Catholic Church for this one relic, this remnant, of her riches, was immense. For this good Protestant water to flow, there had to be Catholic aqueducts. To change the metaphor, I had been told that reliance on external things was a “crutch!” I now realized that I was a cripple. And I thanked the Catholic “hospital” (that’s what the Church is) for responding to my needs.

Perhaps, I thought, these good Protestant people could worship like angels, but I could not. Then I realized that they couldn’t either. Their ears were using crutches, not their eyes. They used beautiful hymns, for which I would gladly exchange the new, flat, unmusical, wimpy “liturgical responses” no one sings in our Masses — their audible imagery is their crutch. I think that in heaven, Protestants will teach Catholics to sing and Catholics will teach Protestants to dance and sculpt.

I developed a strong intellectual and aesthetic love for things medieval: Gregorian chant, Gothic architecture, Thomistic philosophy, illuminated manuscripts, etc. I felt vaguely guilty about it, for that was the Catholic era. I thought I could separate these legitimate cultural forms from the “dangerous” Catholic essence, as the modern Church separated the essence from these discarded forms. Yet I saw a natural connection.

Then one summer, on the beach at Ocean Grove, New Jersey, I read St. John of the Cross. I did not understand much of it, but I knew, with undeniable certainty, that here was reality, something as massive and positive as a mountain range. I felt as if I had just come out of a small, comfortable cave, in which I had lived all my life, and found that there was an unsuspected world outside, of incredible dimensions. Above all, the dimensions were those of holiness, goodness, purity of heart, obedience to the First and greatest Commandment, willing God’s will, the one absolute I had discovered, at the age of eight. I was very far from saintly, but that did not prevent me from fascinated admiration from afar; the valley dweller appreciates the height of the mountain more than the dweller on the foothills. I read other Catholic saints and mystics, and discovered the same reality there, however different the style (even St. Thérèse “The Little Flower”!) I felt sure it was the same reality I had learned to love from my parents and teachers, only a far deeper version of it. It did not seem alien and other. It was not another religion, but the adult version of my own.

Then in a Church history class at Calvin, a professor gave me a way to investigate the claims of the Catholic Church on my own. The essential claim is historical: that Christ founded the Catholic Church, that there is historical continuity. If that were true, I would have to be a Catholic out of obedience to my one absolute, the will of my Lord. The teacher explained the Protestant belief. He said that Catholics accuse us Protestants of going back only to Luther and Calvin; but this is not true; we go back to Christ. Christ had never intended a Catholic-style Church, but a Protestant-style one. The Catholic additions to the simple, Protestant-style New Testament Church had grown up gradually in the Middle Ages like barnacles on the hull of a ship, and the Protestant Reformers had merely scraped off the barnacles, the alien, pagan accretions. The Catholics, on the other hand, believed that Christ established the Church Catholic from the start, and that the doctrines and practices that Protestants saw as barnacles were, in fact, the very living and inseparable parts of the planks and beams of the ship.

I thought this made the Catholic claim empirically testable, and I wanted to test it because I was worried by this time about my dangerous interest in things Catholic. Half of me wanted to discover it was the true Church (that was the more adventurous half); the other half wanted to prove it false (that was the comfortable half). My adventurous half rejoiced when I discovered in the early Church such Catholic elements as the centrality of the Eucharist, the Real Presence, prayers to saints, devotion to Mary, an insistence on visible unity, and apostolic succession. Furthermore, the Church Fathers just “smelled” more Catholic than Protestant, especially St. Augustine, my personal favorite and a hero to most Protestants too. It seemed very obvious that if Augustine or Jerome or Ignatius of Antioch or Anthony of the Desert, or Justin Martyr, or Clement of Alexandria, or Athanasius were alive today, they would be Catholics, not Protestants.

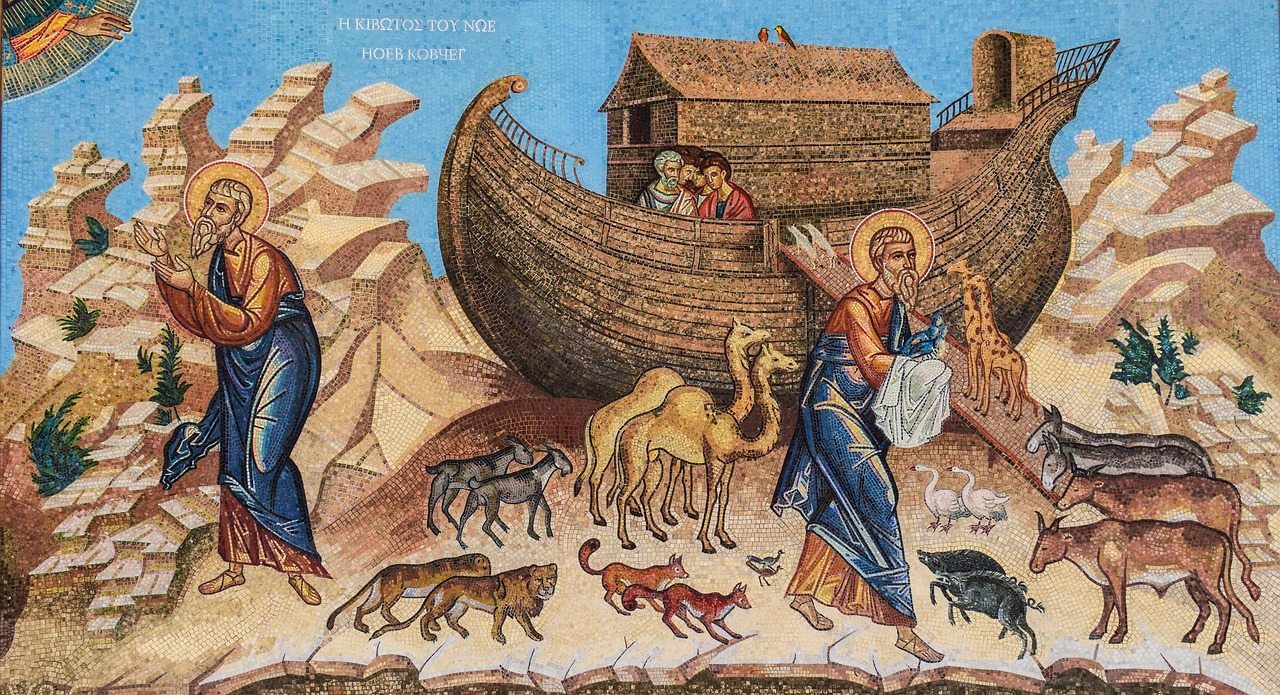

The issue of the Church’s historical roots was crucial to me, for the thing I had found in the Catholic Church and in no Protestant church was simply this: the massive historical fact that there she is, majestic and unsinkable. It was the same old seaworthy ship, the Noah’s ark that Jesus had commissioned. It was like discovering not an accurate picture of the ark, or even a real relic of its wood, but the whole ark itself, still sailing unscathed on the seas of history! It was like a fairy tale come true, like a “myth become fact,” to use C. S. Lewis’ formula for the Incarnation.

The parallel between Christ and Church, Incarnation and Church history, goes still further. I thought, just as Jesus made a claim about His identity that forces us into one of only two camps, His enemies or His worshippers, those who call Him liar and those who call Him Lord; so the Catholic Church’s claim to be the one true Church, the Church Christ founded, forces us to say either that this is the most arrogant, blasphemous and wicked claim imaginable, if it is not true, or else that she is just what she claims to be. Just as Jesus stood out as the absolute exception to all other human teachers in claiming to be more than human and more than a teacher, so the Catholic Church stood out above all other denominations in claiming to be not merely a denomination, but the Body of Christ incarnate, infallible, one, and holy, presenting the really present Christ in her Eucharist. I could never rest in a comfortable, respectable ecumenical halfway house of measured admiration from a distance. I had to shout either “Crucify her!” or “Hosanna!” If I could not love and believe her, honesty forced me to despise and fight her.

But I could not despise her. The beauty and sanctity and wisdom of her, like that of Christ, prevented me from calling her liar or lunatic, just as it prevented me from calling Christ that. But simple logic offered then one and only one other option: this must be the Church my Lord provided for me — my Lord, for me. So she had better become my Church if He is my Lord.

There were many strands in the rope that hauled me aboard the ark, though this one — the Church’s claim to be the one Church historically founded by Christ — was the central and deciding one. The book that more than any other decided it for me was Ronald Knox’s The Belief of Catholics. He and Chesterton “spoke with authority, and not as the scribes!” Even C. S. Lewis, the darling of Protestant Evangelicals, “smelled” Catholic most of the time. A recent book by a Calvinist author I went to high school with, John Beversluis, mercilessly tries to tear all Lewis’ arguments to shreds, but Lewis is left without a scratch, and Beversluis comes out looking like an atheist. Lewis is the only author I ever have read whom I thought I could completely trust and completely understand. But he believed in purgatory, the Real Presence in the Eucharist, and not Total Depravity. He was no Calvinist. In fact, he was a medieval.

William Harry Jellema, the greatest teacher I ever knew, though a Calvinist, showed me what I can only call the Catholic vision of the history of philosophy, embracing the Greek and medieval tradition and the view of reason it assumed, a thick rather than a thin one. Technically, this was “realism” (Aquinas) as vs. “nominalism” (Ockham and Luther). Common-sensically, it meant wisdom rather than mere logical consistency, insight rather than mere calculation. I saw Protestant theology as infected with shallow nominalism and Descartes’ narrow scientificization of reason.

A second and related difference is that Catholics, like their Greek and medieval teachers, still believed that reason was essentially reliable, not utterly untrustworthy because fallen. We make mistakes in using it, yes. There are “noetic effects of sin,” yes. But the instrument is reliable. Only our misuse of it is not.

This is connected with a third difference. For Catholics, reason is not just subjective but objective; reason is not our artificial little man-made rules for our own subjective thought processes or intersubjective communications, but a window on the world. And not just the material world, but also form, order, objective truth. Reason was from God. All truth was God’s truth. When Plato or Socrates knew the truth, the logos, they knew Christ, unless John lies in chapter 1 of his Gospel. I gave a chapel speech at Calvin calling Socrates a “common-grace Christian” and unwittingly scandalized the powers that be. They still remember it, thirty years later.

The only person who almost kept me Protestant was Kierkegaard. Not Calvin or Luther. Their denial of free will made human choice a sham game of predestined dice. Kierkegaard offered a brilliant, consistent alternative to Catholicism, but such a quirkily individualistic one, such a pessimistic and antirational one, that he was incompletely human. He could hold a candle to Augustine and Aquinas, I thought — the only Protestant thinker I ever found who could — but he was only the rebel in the ark, while they were the family, Noah’s sons.

But if Catholic dogma contradicted Scripture or itself at any point, I could not believe it. I explored all the cases of claimed contradiction and found each to be a Protestant misunderstanding. No matter how morally bad the Church had gotten in the Renaissance, it never taught heresy. I was impressed with its very hypocrisy: even when it didn’t raise its practice to its preaching, it never lowered its preaching to its practice. Hypocrisy, someone said, is the tribute vice pays to virtue.

I was impressed by the argument that “the Church wrote the Bible”: Christianity was preached by the Church before the New Testament was written — that is simply a historical fact. It is also a fact that the Apostles wrote the New Testament and the Church canonized it, deciding which books were divinely inspired. I knew, from logic and common sense, that a cause can never be less than its effect. You can’t give what you don’t have. If the Church has no divine inspiration and no infallibility, no divine authority, then neither can the New Testament. Protestantism logically entails modernism. I had to be either a Catholic or a modernist. That decided it; that was like saying I had to be either a patriot or a traitor.

One afternoon I knelt alone in my room and prayed God would decide for me, for I am good at thinking but bad at acting, like Hamlet. Unexpectedly, I seemed to sense my heroes Augustine and Aquinas and thousands of other saints and sages calling out to me from the great ark, “Come aboard! We are really here. We still live. Join us. Here is the Body of Christ.” I said Yes. My intellect and feelings had long been conquered; the will is the last to surrender.

One crucial issue remained to be resolved: justification by faith, the central bone of contention of the Reformation. Luther was obviously right here: the doctrine is dearly taught in Romans and Galatians. If the Catholic Church teaches “another gospel” of salvation by works, then it teaches fundamental heresy. I found here, however, another case of misunderstanding. I read Aquinas’ Summa on grace, and the decrees of the Council of Trent, and found them just as strong on grace as Luther or Calvin. I was overjoyed to find that the Catholic Church had read the Bible too! At heaven’s gate our entrance ticket, according to Scripture and Church dogma, is not our good works or our sincerity, but our faith, which glues us to Jesus. He saves us; we do not save ourselves. But I find, incredibly, that nine out of ten Catholics do not know this, the absolutely central, core, essential dogma of Christianity. Protestants are right: most Catholics do in fact believe a whole other religion. Well over ninety percent of students I have polled who have had twelve years of catechism classes, even Catholic high schools, say they expect to go to heaven because they tried, or did their best, or had compassionate feelings to everyone, or were sincere. They hardly ever mention Jesus. Asked why they hope to be saved, they mention almost anything except the Savior. Who taught them? Who wrote their textbooks? These teachers have stolen from our precious children the most valuable thing in the world, the “pearl of great price”: their faith. Jesus had some rather terrifying warnings about such things — something about millstones.

Catholicism taught that we are saved by faith, by grace, by Christ, however few Catholics understood this. And Protestants taught that true faith necessarily produces good works. The fundamental issue of the Reformation is an argument between the roots and the blossoms on the same flower.

But though Luther did not neglect good works, he connected them to faith by only a thin and unreliable thread: human gratitude. In response to God’s great gift of salvation, which we accept by faith, we do good works out of gratitude, he taught. But gratitude is only a feeling, and dependent on the self. The Catholic connection between faith and works is a far stronger and more reliable one. I found it in C. S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity, the best introduction to Christianity I have ever read. It is the ontological reality of us, supernatural life, sanctifying grace, God’s own life in the soul, which is received by faith and then itself produces good works. God comes in one end and out the other: the very same thing that comes in by faith (the life of God) goes out as works, through our free cooperation.

I was also dissatisfied with Luther’s teaching that justification was a legal fiction on God’s part rather than a real event in us; that God looks on the Christian in Christ, sees only Christ’s righteousness, and legally counts or imputes Christ’s righteousness as ours. I thought it had to be as Catholicism says: that God actually imparts Christ to us, in Baptism and through faith (these two are usually together in the New Testament). Here I found the Fundamentalists, especially the Baptists, more philosophically sound than the Calvinists and Lutherans. For me, their language, however sloganish and satirizable, is more accurate when they speak of “Receiving Christ as your personal Savior.”

Though my doubts were all resolved and the choice was made in 1959, my senior year at Calvin, actual membership came a year later, at Yale. My parents were horrified, and only gradually came to realize I had not lost my head or my soul, that Catholics were Christians, not pagans. It was very difficult, for I am a shy and soft-hearted sort, and almost nothing is worse for me than to hurt people I love. I think that I hurt almost as much as they did. But God marvelously binds up wounds.

I have been happy as a Catholic for many years now. The honeymoon faded, of course, but the marriage has deepened. Like all converts I ever have heard of, I was hauled aboard not by those Catholics who try to “sell” the Church by conforming it to the spirit of the times by saying Catholics are just like everyone else, but by those who joyfully held out the ancient and orthodox faith in all its fullness and prophetic challenge to the world. The minimalists, who reduce miracles to myths, dogmas to opinions, laws to values, and the Body of Christ to a psycho-social club, have always elicited wrath, pity, or boredom from me. So has political partisanship masquerading as religion. I am happy as a child to follow Christ’s vicar on earth everywhere he leads. What he loves, I love; what he leaves, I leave; where he leads, I follow. For the Lord we both adore said to Peter his predecessor, “Who hears you, hears Me.” That is why I am a Catholic: because I am a Christian.

Source: “Hauled Aboard the Ark – The Spiritual Journey of Peter Kreeft” excerpt from The Spiritual Journeys, published by the Daughters of St. Paul (1987). Used with permission of the author.

Fantastic story! Dr. Kreeft is one of my heroes and was influential in my own conversion to Catholicism.

Ditto Brandon – What a guy!

“I am happy as a child to follow Christ’s vicar on earth everywhere he

leads. What he loves, I love; what he leaves, I leave; where he leads, I

follow.”

Even to Assisi I, Assisi II, and Assisi III?

“The rebellion must come, stand fast and hold to tradition.” -II Thess ii

I once heard someone say, “If your faith is strong and you truly believe in Jesus, then you would not sin.” Because if your faith is strong and you truly believe that Jesus is your Savior, then you would follow Him and His teachings. Any deviance from this must be the result of lacking faith or belief. Is this a Catholic thought process?

Dear Melanie,

No this is not a Cathoic thought process. As Catholics, we know that we are fallen creatures. Therefore we will sin. It is our faith that keeps us going. We sin, we repent, go to confession and start all over again with hope and our faith as a guide. The Church understands that we will fall again and again. But we must pick ourselves up and continue with the help of Jesus and His Church. We must continually grow in our faith and our understanding of God. It is journey not a “your faith has made you perfect or you have no faith” situation. Only God, Jesus,, the Holy Spirit and the Saints in Heaven are perfect and do no sin.

This is marvelous story of conversion to the One, True, Holy and Apostolic Catholic Church. I will see that my family and friends read it. I am 88 years old and someone introduced me to a book by Peter Kreeft when I was about 60. In these changing times within the Catholic Church, he has been a steady beacon of light to the Church and all its splendor.

But is there a correlation between faith and sin? The greater your faith, the less you sin? And so someone with perfect faith would also not sin… thus the Saints. And if someone continues to find themselves falling to sin, would the best way to end their cycle of sin be to strengthen and grow their faith or simply to resolve, yet again, to not commit their sin?

There is really a correlation between union with Christ and sin. The more we allow God to fill us the less we will sin. God wants to transform us into what Adam and Eve were like in the beginning. The more that we are living in the image of God. The less we will sin. In a sense, by virtue of our baptism and with the help of God’s grace, we can be perfect. “Be perfect as My heavenly Father is perfect.”

I’m trying to figure out why Kreeft calls Peter the predecessor of Christ. At the end of “Hauled Aboard the Ark,” Kreeft states “For the Lord we both adore said to Peter his predecessor, …” Peter is the successor.

Peter is the predecessor of the Vicar of Christ whom Kreeft is “happy as a child to follow”. It’s a tricky sentence.

Abandon the vicar, and you leave the Kingdom. For to whom else will the King return but to His steward? The chair will never be vacant.

If someone continues to find themselves falling to sin, they need to seek Gods grace. God knows we are sinners, but that’s why Jesus gave us the sacrament of penance/reconciliation to receive His grace directly, along with the other sacraments. Especially within the Eucharist: Jesus’ body, blood, soul and divinity is not a symbol but a true reality!, which helps us to sin less. Faith is not something that we do “on our own”, it’s God’s gift to us and requires our reason and an act of our free will to accept Him and allow the Holy Spirit to guide, change and conform us to His will. “His ways are higher than our ways. His thoughts higher than our thoughts.” Our Father knows us better than we know ourselves, He knows what’s best for us.

Similar thoughts makes me extremely interested in Eastern Orthodoxy. The roots run the same. I wonder if Catholicism only wins out because of its dominant presence in the West.

philosophy you say? saying Augustine would have been a Catholic today is odd, since Augustine would have dismissed such a silly premise and ultimately a bad fallacy. (since Augustine himself talked of the time as the mode of God, and would have argued against making the illustration you made in the first place)

Melanie, can you define what you mean by “faith”? Sometimes I think the common use of that words (and the assumptions of what the other person may mean by that) can sometimes lead to confusion. I’d love to understand your question a little bit more! Thank you & God bless!

Teresa, I suspect Melanie may be, without knowing either Bible or theology (it just being something she heard said), obliquely referring to a scriptural passage like 1 John 3:6, 9:

“Any one who abides in him (God) does not sin; any one who sins has not seen him, nor has he known him…. Any one born of God does not commit sin; for God’s seed abides in him, and he cannot sin because he is born of God.”

But of course, this says nothing about “faith.” Instead, it speaks of “abiding” in God and being “born of God.” These expressions are much more in the realm of human behavior under the guidance of divine grace and the Spirit of God than of mere belief or confidence in Christ. But the theological virtue of faith is the door which leads to divine filiation and obedience to the Father, so there is a connection. The words “cannot sin” in v. 9 could simply be taken to mean that, so long as the person does not violate his relationship with God by sinning, he remains a child of God (a tautology), but in more meaningful terms, it probably refers to what Catholics call Predestination to Glory, a state of advanced adherence to God in which the person is assured of persevering to the end in the state of grace (the Gift of Final Perseverance). See the Catholic Encyclopedia article on Final Perseverance at http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11711a.htm.

A similar approach is taken by the Navarre Bible, commenting on the same passage:

“The qualities essential to the Christian life are incompatible with sin; these qualities are — divine filiation (“he is born of God”: v. 9), intimate union with Christ (“who abides in him”: v. 6), and sanctifying grace, together with the infused virtues and the gifts of the Holy Spirit (this seems to be what the expression “God’s nature abides in him” means: v. 9). Thus it is understandable that “No one who abides in him (Christ) sins” (v. 6). In fact, as long as “God’s nature abides in him… he cannot sin” (v. 9). Clearly St. John does not mean that a Christian is incapable of sinning; at the start of the letter he said, “If we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves” (1:8). What he wants to make quite clear is that no one can justify his own sin by the device of claiming to be a child of God (as did the ancient Gnostics).”

Thank you for your thoughts, OnlyOne001. I think it’s really important to ponder what we mean by the word “faith” when saying it — and possibly use a different word or combination of words to express what we mean in a discussion. The word “faith” is incredibly misunderstood, especially in the English language. To some it means closing your eyes and “just believing” and to some it means being in a relationship with someone you trust, and therefore have Faith in (which is more in line the Catholic Catechism’s view: “Faith is man’s response to God”). Regardless wot what the “correct” definition of faith is, it’s really important to understand that when you use “faith” it may be received by your audience in a completely different way, and thus causing problems in communication.

Yes, Teresa, we are agreed that faith is not a mere intellectual “grasping” of a concept of God or things about him, but the establishment of a relationship with him, as outlined in the passage of Scripture I quoted above.

The difference in definitions is like the different uses of the word “love” which we see around us: most of them completely miss the mark. In this we see that it is not merely a communications problem, but something far more fundamental. The profound misunderstanding we see of these elemental concepts has its roots in the rationalistic substitution of an abstract concept of “opinion” for the concrete relation of the human soul to the reality which confronts it.

Melanie, the correlation between faith and sin in my own understanding is the awareness of a sinful act and to make ourselves perfect in the image of Christ. As a correlation the more you grow in faith the more you build out perfection. In other words things, actions, omissions and inactions that we are not aware of to be sinful gradually becomes obvious to us. Thus increase in faith makes us more aware of our sinfulness and sharpen us to greater perfection.

Uchemeze@yahoo